Toxic Teacher by Rita Osborn

book review

This is the story of a music teacher at a Florida community college who got sick with MCS when moving into a newly renovated “tight” building. She battled with the college administration until she was forced to retire nine years later.

Keywords: MCS, chemical sensitivity, workplace, sick building, toxic mold, formaldehyde, pesticides, testimony, history, Rita Osborn

Rita Osborn was 56 years old with five grown daughters when the story starts. She was a music teacher at a community college in southern Florida where she had taught so long she had tenure.

In 1982 she moved into the newly renovated Fine Arts building on the college’s South Campus. This was soon after the energy crises in the 1970s so the renovations made the building much more energy efficient by sealing all windows shut and reducing the flow of fresh air coming through the ventilation system.

The Florida State government gave schools and colleges financial incentives to save energy, besides the money they saved on their energy bills. To save as much as possible, the ventilation systems were completely shut off on weekends.

The lack of ventilation meant the humidity was very high. It was so high books and carpets had visible mold in her office and each Monday morning she had to start the work week by washing mold off her piano and other furniture.

The renovations included new carpets everywhere. Next door was a photographic lab which spewed chemicals she could smell in her office.

Rita soon started having various health problems. Several times her symptoms became so alarming she was taken by ambulance to the emergency room and kept overnight for observation. The doctors were puzzled. Their lab tests didn’t find anything really wrong, though many times her blood oxygen levels were low and she looked sick.

It took a long time for Rita to make the connection with the new building. She had no problems at home, it was only on work days she felt lousy. Other faculty members in the same building also reported problems, though milder than hers.

She kept toughing it out with the result that after two years she had full-blown multiple chemical sensitivity. This is another example that ignoring MCS simply makes it worse over time.

The husband

Rita’s husband of many years owned a small hardware store. He stuck with her through the ordeal, but it was not easy on him either.

He liked to do construction work and it took quite a while for him to really grasp how careful he now had to be. In the early years of Rita’s MCS, he would take the opportunity when she was in the hospital to shampoo the rug, or to paint the walls in their bedroom. He thought she wouldn’t notice what she didn’t know about.

These incidents helped him understand that Rita hadn’t gone nuts on him. The major turnaround was one weekend he went in to take a look at her office himself. Even he felt dizzy in there and had to go home to lie down.

The college administration

Rita finally complained to the management of the college and was stonewalled. Since she was tenured they could not fire her, so they created The Team to contain her. The Team consisted of four people, including the provost and the college lawyer. They told her they had consulted with various experts who assured them that “buildings don’t make people sick.”

This was some years before the Environmental Protection Agency renovated their headquarters in Washington, DC, in 1988. More than a hundred employees got sick and the press had a field day with the story that suddenly made “sick building syndrome” something that could be discussed in the media.

Rita was told she was the only one who complained, even though she knew that wasn’t true. There were other complainers, but since they did not have tenure they were muted. Some were able to change jobs to other buildings, or left the school entirely.

A group of students launched a complaint of their own. When it was brushed off as “mass hysteria” and “crazy” the group threatened with calling the media. Then the college suddenly followed proper procedure and scheduled meetings with each student separately. But, amazingly, they were scheduled at the same time each student had to sit for an exam. They were told the meetings could not be rescheduled. A couple of the students got so mad they got their exams rescheduled. One was then simply told in the meeting that she needed to see a psychiatrist and she really should just give up and stay home with her children instead of raising a fuss (such sexist remarks were more “acceptable” in 1984).

Even after that, the administrators maintained that Rita was the only complainer. They even blamed her for “inciting” the students.

One of her demands was to get the air quality tested. It took three years before they agreed to do so. The test showed high levels of formaldehyde, even three years after the renovations. Well, that MUST be a fluke, so the firm was called back to do another test. The week of the second test everybody felt fine in the building – suddenly a lot of fresh air came out of the registers! Once the firm left, the air again became the same recycled fetid air. Unsurprising, the second test showed minuscule levels of formaldehyde.

The administrators offered her “helpful” advice, such as avoiding orange juice, which is known to harbor mold. But she had not drunk orange juice for years. Other suggestions included taking a class in stress management.

These tactics are not unique and the administrators were probably not particularly evil. They’d just been told by some doctor that Rita was a nutcase, and that was a much more comfortable message than accepting that their buildings were a health hazard. People tend to believe what works for them, regardless whether it is true or not.

Searching for doctors

Rita realized that the doctors she had seen were clueless. She had to search for someone with the right competence. But that was not easy. Through a sympathetic doctor she was told about a psychiatrist who had MCS himself. He reassured her she was not going crazy, but could offer little help.

She talked to various allergists. Since there was a turf war going on between allergists and physicians who practiced environmental medicine, she got some hostile responses.

She discovered the book An alternative approach to allergies, by Theron Randolph, the father of environmental medicine. She brought it along to show the physicians. One said it was “folderol” and “not scientific.” When she asked if he had read it, the physician replied “no … but I know everything that is in it.” He also told her that “buildings don’t make people sick.”

Another doctor responded with icy silence. Then he told her there weren’t any physicians practicing such medicine in their part of Florida (there were actually three).

Eventually a sympathetic allergist gave her the name of the right physician, who was able to help her manage the illness for many years. But there was no cure.

Holding out

Rita really wanted to hold out until she could retire at age 65. With the medical bills accumulating she also needed the money, but of course her workplace caused the bills. She loved her job and couldn’t see herself sitting at home all day.

On page 165 she says:

… I pondered the million dollar question, ‘Is it worth taking all of these chances? Wouldn’t it make more sense to stay home and feel better? Not for me it wouldn’t.’

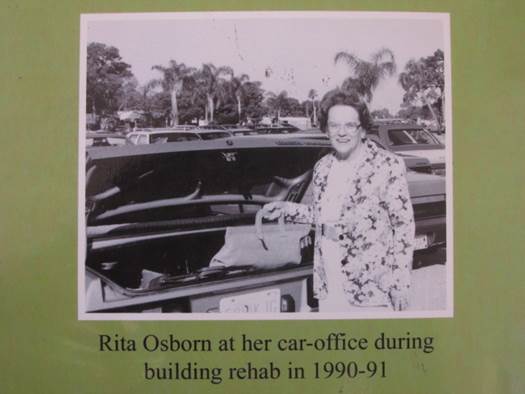

The college eventually became more accommodating and allowed her to move to other buildings, but the pest exterminators chased her out again multiple times. At one point her car became her office for a year, while she taught in a large auditorium. The buildings were sprayed with the pesticide Dursban, which was banned a decade later.

She enacted a no-fragrance policy in her classroom and the students generally complied (personal care products became much worse later). But it was not easy. One student was so proud of her new hair mousse, which caused serious trouble for Rita.

People smoked inside buildings back then, which was another problem.

Sometimes the inside air was so fetid even many of the students felt dizzy. Some enterprising student brought along tools to completely remove a window for the class session, and then put it back in place afterwards.

Retirement

Rita was forced to retire in 1991, when she was 64 years old, instead of her goal of 65 (the age she became eligible for Social Security). What forced her out were renovations of the last buildings she was able to be inside. The buildings would be sealed up like the others.

One remaining “safe” building was “tented,” where a giant tent was erected around it and the insides soaked in pesticides to root out termites. She simply had to give up after battling the college for nine years.

Her husband’s hardware store had for years been squeezed by a big chain store that came to town, so he closed down the store. He then renovated an old travel trailer and the couple spent the summer traveling the country and visiting friends and family. They visited a few people with MCS who had moved away to rural areas, such as in North Carolina.

Activist work

A year into retirement Rita started an MCS support group as a local chapter of the national HEAL organization. The group quickly grew to 80 members and had its own newsletter.

This was 1992, the heyday of MCS where the illness was getting sympathetic media coverage and politicians were willing to talk to the MCS community (it didn’t last long, the chemical industry launched on effective anti-campaign in those years, but that’s another story).

She spent a lot of effort on the support group where some of the common issues were where to get organic foods and other necessities not available in local stores.

She wrote a lot of activist letters to companies, and many of them actually responded. One thing she found out was that socks labeled “100% cotton” could actually contain up to 5% synthetic fibers – which explained why some itched so much.

She was part of the push to get an official pesticide registry set up in Florida, where lawn care companies had to notify people with MCS when they were spraying within a quarter mile (400 meters) of their home.

The local companies were very upset about this. Rita once received a death threat and she was stalked. Several times pesticides were dumped outside her house at night. It was not her imagination, a disgusted insider told her what was going on.

She toned down her activist work and did part time work teaching music and playing for choirs and other public performances in buildings she tolerated.

One time she had to sit guard over a dying friend in a hospital. The friend had severe MCS and every time a certain highly fragranced nurse came into the room, the vital signs got worse. The medical staff noticed this, but refused to accept the likely cause. This was around year 2000, when fragrances had become much more powerful.

Afterword

Rita Pangborn Osborn died November 17, 2017 at the age of 91. The obituary in the Tampa Bay Times revealed what she studiously avoided saying in her book: the college she taught in and fought for so many years was St. Petersburg Junior College, which is now called SPC. She lived until her death in St. Petersburg, Florida.

Her book, Toxic Teacher, was published in 2009. It was apparently self-published as it lists no publisher, ISBN number or Library of Congress information. We were only able to obtain a copy second hand.

More information

Other MCS/EI book reviews are available on www.eiwellspring.org/booksandreviews.html

Personal stories can be found on www.eiwellspring.org/facesandstories.html

2023