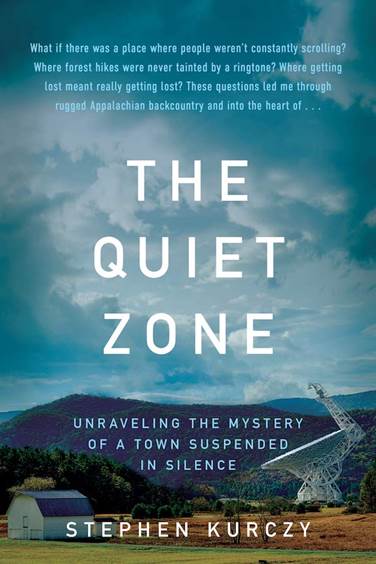

Tensions and electrosensitives in America’s only true low-EMF zone – review of The Quiet Zone by Stephen Kurczy

A radio-free zone protects an astronomical observatory from interference. It also became a refuge for people with severe electrical hypersensitivity. This story is a lesson for anyone dreaming of creating a low-EMF zone elsewhere, and a cautionary tale about opinionated journalists.

Keywords: Green Bank, white zone, electrical sensitivity, media, journalist, Stephen Kurczy

The National Radio-Quiet Zone at Green Bank in West Virginia is the only legally protected low-EMF zone in the United States. It was created in the 1950s to protect a large radio observatory, as local radio transmitters would otherwise drown out the weak signals from distant galaxies.

Since cell phones do not work there, it is also sometimes referred to as a “white zone.”

There are other radio observatories in the United States, but they have to rely on the friendly cooperation of their neighbors, and the commercial mobile service providers. It proved too politically difficult to create more legally protected zones in this country, while there are a few in other countries, such as Australia and South Africa.

Stephen Kurczy is a New York journalist who is critical of the “always connected” lifestyle and smartphones. He decides to investigate what life is like in a place where smartphones don’t work.

He spends a combined total of four months at Green Bank, spread over the years 2015 to 2018. He finds all kinds of people live in the area, including regular rural folks, hippies, neo-Nazis, charlatans, suspected murderers, electrosensitives and more.

This review focuses on Kurczy’s description of the electrosensitives, which he spends the prologue and three chapters on, plus a sprinkling in other chapters. He also reports on the problems the Green Bank observatory has maintaining the radio-quiet they need.

The Quiet Zone is in Pocahontas County in a remote part of West Virginia. The local folks have often lived there for generations and are poor and culturally conservative, but they don’t seem to mind outsiders with strange opinions settling there. The ethos is “live and let live,” according to Kurczy.

But it is an all-white community, with the Confederate flag commonly shown. A Puerto Rican who moved there to work in a lumber mill tells how that feels:

There’s one bar and you go and they all look at you like they want to fight with you.

Protecting the Quiet Zone

The Quiet Zone is continually challenged and the observatory is tasked with pushing back against these challenges.

The book has a whole chapter about how the observatory’s engineers have worked with people and businesses to reduce the electrosmog. One major project was setting up a large number of low-power transmitters on the slopes of the local ski resort, so guests could use their cell phones on the slopes.

When the local school in Green Bank got internet service, engineers from the observatory did the installation. They also shielded the school’s outdoor electronic sign.

Repairing electrical power poles is an ongoing task, as rusty hardware can generate arcing.

On the grounds of the observatory, they shielded a lot of equipment, such as electrical motors, LED signs and microwave ovens.

Tall pines were planted around the observatory to absorb incoming radio waves. The observatory is located in a bowl that shields it from the surrounding area.

But there are people living there too, who are asked to not pollute the ether.

The observatory management is keenly aware that their presence imparts limitations on the local residents, and tries to be a good neighbor. They host an annual hunt on their 2700 acre grounds, they host various fairs, proms and other events in their facilities. The local kids learn to swim in the observatory’s swimming pool. When there are prolonged power outages and other emergencies, the staff helps the community. The staff sometimes speak at the local schools and volunteer to coach science clubs.

The observatory is an important employer, with a year-round staff of a hundred, plus dozens of temporary jobs during the summer tourist season. It brings a lot of money to a county with a high poverty rate.

Despite all this, there is still resentment and people defy the rules anyway. Kurczy drives around the area with a Wi-Fi detector and is astounded that nearly every house has a wireless network.

One house just outside the observatory has a Wi-Fi network named “Screw you NRAO” (the observatory is operated by NRAO).

Even the local school uses Wi-Fi. It started because one student needed a wireless medical monitor. Then the staff started using the network too.

These people are all clearly breaking state law, but the observatory never brought charges against anyone. That would surely backfire.

The observatory had to abandon that part of the electromagnetic spectrum. But the challenges continue, with people wanting cell services everywhere, which would further limit what the observatory can detect from space.

The lesson for anyone who dreams of creating low-EMF zones in even lightly populated areas is that it’s not possible. At least not in the United States. When people even defy an observatory that provides so many benefits to the community, how much would they care about people that are easy to write off as freaks.

As Kurczy states:

For every electrosensitive who wanted radio quiet, there were probably one hundred residents who wanted WiFi and cell service.

A real problem in Green Bank was that the internet available through cables was much slower than what was available through wireless cell service right outside the zone. Even if that was corrected, it seems people wanted the convenience of wireless regardless. Ethernet cables to a laptop computer were just too inconvenient.

Despite poverty and difficulty getting a signal, every kid in a middle school class he visits had a smartphone.

The observatory had to fire one of its own employees who refused to stop using his own Wi-Fi network inside the observatory, which had a good cable-based internet service.

The electrosensitive community

How many people with electrosensitivity live in the Zone is unknown. Some move there and keep really quiet about their illness, due to the stigma.

A local realtor estimates that ten percent of real estate sales go to people with electrosensitivity.

There may be about a hundred people in total. Two dozen, plus spouses, showed up for a Christmas party Kurczy attended.

The first who moved there was Diane Schou, who arrived in 2007. She has since appeared in many newspapers, magazines and television channels from several countries.

The local people tolerate the electrosensitives, though one of them quickly wore out her welcome by being very demanding. She even sued the local medical clinic over EMF accessibility issues (and lost).

Some locals thought she was trying to impose “electromagnetic sharia law” on the community. That was not a good strategy in a conservative rural area where everybody knows everybody. It was just one person, but it tainted everyone with the illness.

As it is everywhere, the majority imposes certain things upon any minority, and considers it fair, just, and “the way things are” – and deeply resents anything coming the other way.

The county attorney called the electrically sensitive:

Wackos that are afraid of their brains getting fried…

The local newspaper, Pocahontas Times, refuses to mention the electrosensitives, except for one early article about Diane Schou. The library refused to put books donated by the electrosensitives on its shelves.

A local mayor, who wanted better cell phone service in his town, stated:

Maybe Pocahontas county is not remote enough for their situation … Well, we’re already being sensitive to the requirements of Green Bank, and to do any less is to keep the majority from being serviced because of a very small population,

What Stephen Kurczy thinks

In chapter twelve (“Murder by WiFi”) Kurczy lays out his case for not believing the people with electrical hypersensitivity. It is completely one-sided and mostly based on his own observations of the local community. He never allows anyone who accepts the illness to respond to his observations and assertions. There is never anything that supports the electrically sensitive people, other than their say-so.

Diane Schou is the most outspoken member of the electrosensitive community. Kurczy meets with her multiple times. One time he has lunch with Diane and her husband Bert at a restaurant in Marlinton (just south of the zone). He knows the restaurant has Wi-Fi, so why is Diane eating there when she says Wi-Fi hurts her?

This is a common type of observation journalists and others make, which makes them decide the electrosensitives are not credible.

He never asks her about it, which is a pity, as there could be several reasonable explanations. Diane Schou is intelligent and undoubtedly knew there was Wi-Fi. She probably also knew where the transmitter was, and made sure to be seated far from it.

EMF exposures are like the sun’s rays on pale skin. It accumulates. It may be okay for one hour, but not all day and maybe not even every day.

There are other possible explanations, but they are harder for healthy people to understand.

At least the Covid lockdowns should have taught Kurczy that people get fed up with restrictions and sometimes are willing to take risks.

None of these reasonable explanations occurs to Kurczy, which is not surprising since he is an outsider. But why doesn’t he simply ask?

He interviews a woman named Sue, using an iPod to record the conversation. After a while, Sue says her veins “pop,” but Kurczy can’t see anything different, which he uses to discredit her. This reviewer has often had blood drawn in medical clinics by technicians struggling to get the veins to “pop.” When they did, I could never tell the difference either.

He talks to an engineer at the observatory, who says she doesn’t believe in electrical sensitivity “because the people who have it have such a vast array of symptoms.” And yet, cigarettes can produce more than two dozen diverse symptoms, such as low birth weight, high blood pressure, premature aging of skin and several type of cancer. Some autoimmune diseases can produce very diverse and changing symptoms. More than two hundred symptoms are attributed to Long Covid.

He tells many other anecdotes that are also not as clear cut as he thinks.

He asks Schou for proof that the illness is “real” and is told there are twenty thousand studies supporting it. He might have misunderstood what was said, as the number is two thousand and they demonstrate biological effects, not necessarily illness.

He is given a copy of a landmark 1991 study by Dr. William Rea and six colleagues. He quickly dismisses it citing the trouble Dr. Rea faced with the Texas medical board as discrediting everything Rea ever did. Likewise he also dismisses Dr. David O. Carpenter’s work. He read the book Overpowered by Dr. Martin Blank, but dismisses it by citing some comments about glasses increasing brain exposure to radio waves. Again, he jumps to conclusions. To this reviewer’s surprise, there is real science to support this for glasses with metal frames, but Kurczy apparently didn’t check.

Kurczy cites a notorious review of exposure studies as a final dismissal. This review is done by Dr. Rubin who is one of the most ardent opponents of electrical hypersensitivity (and other controversial diseases).

Unfortunately, Kurczy takes the critics at face value, and does not apply the same skepticism he applies to those who support the legitimacy of electromagnetic hypersensitivity. It would be quite illuminating if he had applied the same standard and looked into their motivations and methods, including the dodgy Texas medical board case.

He dismisses everything that supports the existence of electrical hypersensitivity in just a few pages.

He never interviews any scientists or physicians who treat people with the illness. He read Dr. Martin Blank’s book. Blank was at Columbia University near Kurczy’s home; it would have been easy to visit, but he did not. Apparently Kurczy thinks his own perceptions are sufficient.

Some of the people he meets appear to be their own worst enemy, as Kurczy tells it. He spends pages describing how Diane Schou acts eccentric and kooky.

Another electrosensitive, whom Kurczy considers the most credible, told him she had called the observatory several times when she felt bad. In her telling, they confirmed that there was a problem. Kurczy called the observatory, which could only partially confirm the story, and said that there was no way to really tell, which is quite sensible.

During the Covid-19 epidemic Kurczy talks to some of the electrosensitives in Green Bank. Several of them told him that “Covid-19 was linked to cell towers and 5G.” That was another stupid conspiracy theory, and Kurczy uses it to discredit the electrosensitives.

Kurczy discredits a man with electrical sensitivities by listing the conspiracy theories he believed in. They were all common theories at the time, mostly involving Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton. The man was a local farmer who lived there long before he got sick. What he says are undoubtedly common beliefs in Pocahontas County, but Kurczy never mentions that. In his telling, it is only those supporting the electrically sensitive who hold wacky beliefs (apart from the few neo-Nazis).

It is possible that the regular folks were smart enough to not tell these ideas to a journalist from New York, but it seems more likely that Kurczy is being selective to fit his agenda.

This reviewer lives in rural Arizona. Here the same theories about Obama and Clinton are fully mainstream. And there are many more. One story is that the local wind farm uses more electricity than it produces. Apparently, people observed that the blades spin even when there is no wind, so they concluded the blades are run by electromotors and it is all a fraud. In reality, there is wind up by the blades, even if there is none by the ground. It is called “high windshear.”

People who know little can easily draw incorrect conclusions from what they observe. Just as Kurczy apparently does.

What journalists do not seem to understand is that just because someone becomes sick does not mean that they have also become an expert on their illness (and physics, and biology, etc.)

In the absence of good information, people make up their own explanations, often aided by various echo chambers. That is a common feature of poorly understood illnesses, with past examples including AIDS and tuberculosis.

When the Chernobyl nuclear power plant spewed radioactivity in 1986, the doctors told people with radiation sickness it was just anxiety. So people made up wacky explanations and treatments. That is what people do when the “authorities” are no help at all.

Kurczy uses a double standard. The electrosensitives are held to a much higher standard than other people. That also goes for the physicians who try to help them.

He also never considers what it can do to people when they get sick, doctors downplay and blow them off, they are constantly bodily attacked, and they have to flee their homes. Such experiences will, at best, make people look at the world differently. And that can account for much of the eccentric behavior Kurczy reports.

Also consider that people who are willing to take the inevitable flack from stepping outside the quiescent herd tend to be mavericks, and often step on the toes of authority figures.

Late in the book Kurczy writes:

The electrosensitives seemed to be fleeing something in their lives aside from electromagnetic radiation.

He never explains what he thought they were fleeing from. Or who suggested this to him. It sounds like a resurrection of the popular myth from the 1990s that people with multiple chemical sensitivity were all fleeing from childhood abuse, which was debunked by the Bailer study in 2007.

Conclusions

The Quiet Zone is an easy read about the people living in the shadow of the Green Bank observatory. It is similar to Jessica Bruder’s bestselling Nomadland in several ways, but Bruder gets much closer to the people she writes about. She also doesn’t try to judge people, including one with MCS.

In contrast, Kurczy’s reporting on the electrosensitives is biased and rather one-dimensional. It is all about how he perceives their illness and personality flaws. He is more respectful of the neo-Nazis than he is of the electrosensitives.

Kurczy’s major mistake is that he requires the sick people to be paragons to be taken seriously. That used to be the case for victims of rape and domestic abuse; he still applies it to the electrosensitives, and the physicians who try to help them – and not to their critics.

His publisher employed a fact checker, but a couple of mistakes still made it through. Download speeds are always higher than upload speeds. Li-Fi is not a low-power version of Wi-Fi, but uses visual light to transmit. We all make mistakes, but Kurczy doesn’t seem to allow that for the electrosensitives.

Even though Kurczy spent a combined four months in Green Bank, he is very much an outsider, which the editor of the local newspaper tried to make him understand. That doubly goes for an illness he does not live with himself, and knows virtually nothing about, but of which he still thinks he can be the judge.

He should have asked about what he sees as “inconsistencies” rather than arrogantly assuming he understands enough to determine what is “real” or not.

At the end he lists a great number of books he read about neo-Nazis and West Virginia history. But nothing at all relevant to electrical hypersensitivity.

He earlier stated he read Martin Blank’s Overpowered, but he clearly ignored everything in it. Instead Kurczy watched the TV series Better Call Saul, which is fiction and a mean-spirited trashing of people with electrical hypersensitivity.

He states he got a lot of information from newspaper articles. There are several about the people with electrosensitivity in Green Bank. They are certainly convenient, but they too were written by opinionated journalists who couldn’t be bothered to read a book about the subject. So, Kurczy just added another piece to the media echo chamber.

More information

Other articles about hostile media and the harm it creates are on www.eiwellspring.org/media.html

Reviews of other books about living with environmental illnesses on:

www.eiwellspring.org/booksandreviews.html

2022