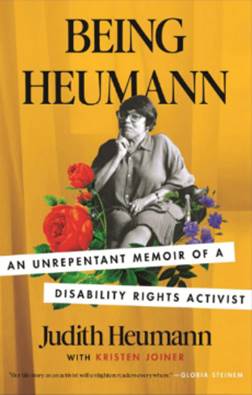

Being Heumann – the story of a disability civil rights hero and what we can learn from her

book review

Judith Heumann was deeply involved in getting the two most important laws about disability civil rights through. Her story is an inspiration for those advocating for people with environmental disabilities.

Keywords: Judith Heumann, disability rights, civil rights, Section 504, Americans with Disabilities Act, activism

Judith Heumann contracted polio when she was 18 months old. The disease paralyzed her, and left her in a wheelchair for life.

In the 1950s there was a stigma to any disability. It was viewed as your own fault or the fault of your parents.

Disabled kids were not normally schooled, it was seen as pointless, so there were only a few schools that accepted them. Judy’s mother was finally able to get a place for her by fourth grade. At that time Judy had learned so much at home she was reading at the high school level, while many of her class mates were far behind. The school was almost like a warehouse of disabled people, they were not expected to learn much.

When she got to high school and later college, the buildings were not at all accessible to wheelchairs. There were steps everywhere and she had to rely on her classmates to get around, and even into the bathrooms.

In her college dorm she sometimes had to go from door to door to find someone to help her get into the bathroom.

The birth of an activist

Judy was involved in campus protests against the Vietnam war in the late 1960s. She learned about activism there.

When she graduated in 1970, she wanted to teach second grade, so she applied for a teaching license from the New York City Board of Education. She passed all the written tests, and then there was a medical exam to make sure she wasn’t a carrier of disease or otherwise a danger to the children. The exam was a very humiliating experience with many deeply personal questions that were not relevant. Then she was rejected because she couldn’t walk.

That was the last straw. She had run into all sorts of barriers all her life without complaining, but this one was so mean and blatant she decided to fight.

She called the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), which defends civil rights through the court system. Their response was:

I’m sorry, Miss Heumann. We’ve considered your case and determined that no discrimination has occurred. You’ve been denied your license for medical reasons, which is not discrimination.

She was on her own to fight the injustice, but how? She knew someone who worked for The New York Times, so she called him. They sent a journalist who wrote a large and sympathetic article. That started a firestorm. The whole press went behind her, pointing out that Roosevelt had polio too and he was not excluded from becoming president.

She became a minor celebrity, easily recognizable in her wheelchair, with people cheering her on. Attorneys called to volunteer their services.

The Board caved in after the first court appearance where it was clear the judge had no sympathy for them. Had it been another judge, this story could have ended here.

But Judy had to search a long time before a school was willing to hire a disabled teacher. However, once in, it went very well. She taught both disabled and regular kids, who had never seen a teacher in a wheelchair before. She was the first in New York.

The ordeal inspired Judy to fight other discrimination against the disabled, so she co-founded an activist organization which had about eighty active members in New York. They protested how disabled people were portrayed on television, Richard Nixon’s veto of the 1972 Rehabilitation Act, that wheelchairs could not go on buses and subway trains, and that people were institutionalized when they didn’t need to be.

After some years she moved to Berkeley, California to get a Master’s degree in public health and work for a new organization that organized support for disabled people so they could live in their own homes without being dependent on family help.

Berkeley was very liberating for Judy. It had a whole community of disabled people so she could socialize as never before. The services provided there were also much better, so she didn’t have to rely on favors all the time and she now had the freedom to decide such basic things as when she went to bed, when to bathe, and when to visit friends. It was a much more dignified way to live, though quite radical in those days.

From there she moved to Washington, DC, to work for a senator from New Jersey. The senator was very supportive of disability rights and needed someone with actual experience being discriminated against.

Such experience kept coming, such as the time she was thrown off a plane because of her disability. They wouldn’t allow her to travel as she could not run off the plane in case of an emergency.

She knew this was illegal and stood her ground, so security had to be called. They got cold feet once they saw her US senate ID (she had no driver’s license), but by then the plane had left. She took them to court, but the judge accused her of staging the event and had little sympathy.

Section 504

The Rehabilitation Act was signed into law in 1973. It had a provision that any institution that received federal funding could not discriminate against people with disabilities. The provision was referred to as Section 504.

The Section was sneaked into the law, so there wasn’t much debate about it, and little opposition.

A new law doesn’t actually take effect until a government agency issues guidelines on how to actually comply.

Schools and universities were strongly opposed to installing wheelchair ramps and other measures. Their political muscle got the Federal bureaucrats to sit on the guidelines.

After four years of waiting, the disability community started protesting. This was in 1977.

Judy was a central person in the battle that ensued. It takes up a third of the book and is fascinating reading that is vividly told.

The basic story is that a motley crew of disabled people took over parts of the Federal building in San Francisco and refused to leave unless the guidelines were signed off on. This was completely unprecedented, as there were well over a hundred protestors who were dependent on wheelchairs, sign language interpreters, personal assistants, catheters, white canes, and much else. It was not a group that could just go camping.

Their opponent was one single top-level bureaucrat in Washington, DC, who realized it would be a media disaster if he got the police to throw the protesters out. Instead, he tried all sorts of tricks to make them leave, such as cutting off the phones, blocking food deliveries, and even a fake bomb threat. The tactics worked for the other occupied buildings in Washington, Denver, and Los Angeles, but the San Francisco group had too much local support, both by the employees in the Federal building, and the wider community. And they were quite inventive, such as using sign language to communicate out the building when the phones were cut.

An official suggested a compromise, where a few schools and universities would become accessible. He even used the phrase “separate but equal” which had been used to justify the racial segregation in the South. That did not go over well as everybody well knew there would be no “equal.”

Their opponent continued to refuse to talk to them. Officially, he pretended they did not exist. As Judy writes:

When someone ignores you, it’s an intentional display of power. They’re essentially acting like you don’t exist, and they do it because they can. They believe that nothing will happen to them. Ignoring silences people. It intentionally avoids resolution or compromise. It ignites your worst fears of unworthyness because it makes you feel that you deserve to be ignored. Inevitably, being ignored puts you in the position of having to choose between making a fuss or accepting the silent treatment. If you stand up to the ignorer and get in their face, you break the norms of polite behavior and end up feeling worse, diminished, demeaned.

And that is what they did. They kept turning up the volume until they could not be ignored. By then they had national media coverage, much sympathy in Congress, a meeting in the White House, candle light vigils in front of the opponent’s house, and much else. It was all done peacefully. There were no arrests.

After three weeks and much drama, they finally won a complete victory. They were plucky, persistent, inventive, brave, and unified. And they were very lucky too, to pull this off.

The Americans with Disabilities Act

Section 504 only covered institutions that received federal funding, it did not cover movie theaters, shopping malls, bus companies, work places, housing, and much else.

Disabled people were left out of the 1964 civil rights law. Judy worked for nine years to rectify that with the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). When it needed a final push to get out of committee, they organized a public display where sixty disabled people crawled up the 83 steps in front of the U.S. Capitol in Washington, while a thousand people cheered them on.

Four months later, President George H. W. Bush signed the law at a large outdoor ceremony. He said:

Let the shameful wall of exclusion finally come tumbling down.

That was in 1990; people with environmental disabilities are still waiting for that wall to come down for them.

Policy wonk

After the passing of the ADA, Judy’s career really took off, giving her more opportunity to promote civil rights for people with disabilities.

She worked in the Clinton administration, where she oversaw a staff of four hundred. Then on to the World Bank, and then the Obama administration.

Lessons for the EI community

This book is an inspiration for the community of people with environmental disabilities. We are still faced with all sorts of walls, still being ignored and looked down upon, just as Judy describes it.

Judy points out that the disabled people had to change their thinking to see the injustice:

People had to get out of the habit of thinking “I can’t get up the steps because I can’t walk” and get used to thinking “I can’t get up the steps because they’re not accessible.”

That is a lesson we with environmental illnesses need to learn too. Change is possible, but it doesn’t come on its own.

Many public actions are probably not realistic. Public offices are rarely accessible to people with severe environmental disabilities, especially not for a longer stay. The bad guys can just walk around with a can of Febreeze or Raid to clear the place.

These kinds of actions are also for young people. Judith was about 28 years old in 1977, and so were the other activists. When people get an environmental illness, they are usually in their mid-thirties or later, and it then takes years to get to a point where it is possible to do something other than surviving.

At the end of the book Judy stresses that these things did not happen just because of a few people, and they took years of organizing and building relations with allied groups. It would not have happened without broad support, including from the media.

More information

More environmental illness book reviews on: www.eiwellspring.org/booksandreviews.html.

More about EI activism: www.eiwellspring.org/activist.html.

2024