A history of Doctor William Rea’s Environmental Health Center - Dallas

Doctor William Rea was a pioneer in treating people with environmental illnesses. He opened his Environmental Health Center - Dallas in 1974, which he operated until his death in 2018. The clinic grew tremendously and a whole ecosystem of businesses sprung up around it to serve his patients.

Keywords: William Rea, environmental health center, environmental medicine, history

Dr. William Rea

Dr. Rea originally came from Ohio, where he first studied at Otterbein College and then received his medical degree from the Ohio State University in 1962.

He then moved to Dallas, Texas, where he spent the next seven years as an intern and resident in surgery at the city’s major medical institutions. This included specialization in thoracic and cardiovascular surgery.

Rea went on an academic career with professorships in surgery at the University of Texas, besides being chief of surgery at the local Veterans Hospital and later Brookhaven Hospital. He published twenty-three articles about surgery in medical journals in the years 1966 to 1972.

The wounded healer

Rea contracted polio early on, which left him with a permanent limp, but it didn’t slow him down. In the early 1970s he developed multiple chemical sensitivities (MCS), which he thought was caused by daily exposures to anesthesia gases leaking from the masks patients wore while he operated on them.

He traveled to Chicago to the clinic of Dr. Theron Randolph, who was the original pioneer in treating MCS.

Randolph’s methods helped tremendously. Rea was a purist and liked to experiment on himself. He once slept in a tent in his own backyard for a month. Another time he went on a 21-day rotation diet where he ate only one meal a day, which consisted of just one ingredient.

Despite the successful treatments, he had to be careful for the rest of his life. He could tolerate the toxic air in Dallas and on airplanes, but he still needed to spend most weekends in the pristine air at his ranch on the east side of Lake Tawakoni, where he slept in a large porcelain trailer.

He also ate an organic diet as much as possible. He even had his own herd of organic cows on his ranch for a while.

The clinic

Impressed by Dr. Randolph’s methods, Rea decided to practice environmental medicine himself (which was called “clinical ecology” in the early days). He started his own practice.

The building with EHC-D on the upper floor

Rea’s Environmental Health Center - Dallas opened in 1974. It was located across the street from Presbyterian Hospital, in a professional building at 8345 Walnut Hill Lane in Dallas.

He chose a building that was set well back from the road, and he persuaded the management of the development to not spray the small lawn in front of the building.

The clinic was state-of-the-art non-toxic construction at the time. The walls and ceilings were all covered by steel panels with a porcelain coating. The floors were terrazzo tile. It cost a fortune to use these materials. According to Rea, he spent about a million dollars building his clinic.

Patient examination room

The clinic grew over the decades. Originally it was just suite 205, which covered about a quarter of the upper floor of the building. Gradually he took over the entire floor of 15,000 square feet (1500 sq. meters), and also a 1200 sq. ft (120 sq. meter) lab in the adjacent building.

At its final size it had two allergy testing rooms, two patient waiting rooms, library, archive, several treatment rooms and laboratories, and a section with exercise equipment and three saunas.

Whenever the clinic expanded, new building methods were tried. The second waiting room had all-glass walls. The sauna area had less-toxic vinyl floor tiles produced in France. The main hallway had aluminum wallpaper with a printed motif for many years, until it was replaced with ceramic wall tiles.

Hallway through building, with tiled walls

Waiting room with porcelain walls, terrazzo floor and large air purifier

For some years there was also a satellite clinic in Texarkana on the border to Arkansas. It was taken over when the original owner, Dr. Maley, died. It was not profitable and was shut down around 1992.

The environmental control units

Dr. Randolph in Chicago realized some patients were so sensitized they reacted to just about everything. They felt sick all the time and it was very difficult to figure out what caused their symptoms. In response he came up with the idea of the environmental control unit (ECU), which was a special hospital ward where the food, water, and air were as pristine as possible.

The first such ECU was opened by Dr. Lawrence Dickey in Fort Collins, Colorado in 1975. Rea opened one in Dallas just a few months later. Rea’s first ECU was at Brookhaven Hospital and had 20 beds. It had to be sealed off from the rest of the hospital as people smoked in the ward next door.

The patients were kept in isolation from the outside world for weeks and were served individualized organic meals and water in glass bottles. By removing as many triggers as possible, the patients usually felt much better and could gradually determine all the things that made them sick.

We are not sure when Rea’s Brookhaven ECU closed, but it was still operating in 1980 (Temple 1980).

Rea’s second ECU was at Carrollton Community Hospital from 1982 to 1983. It was followed by an ECU at Northeast Community Hospital in Bedford from 1984 to 1987. His last ECU was at TriCity Hospital from about 1997 to 1998. That was apparently the last ECU in the world; they were simply too expensive to operate and health insurers refused to pay.

See the link at the bottom of this article for more on ECUs.

Dr. Rea was an unusual doctor

Dr. Rea was not like most doctors. The first consultation took an hour, where he encouraged the patient to talk while he listened. He wanted to know everything; the whole long story.

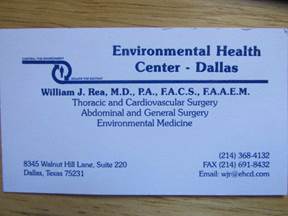

Dr. William Rea’s business card

This was in accordance with the teachings of Dr. Theron Randolph, who said that if the doctor listened closely to the patient, the underlying problem would reveal itself. This is in contrast to the typical American physician who cuts off the patient after twenty seconds.

If a new patient showed up with a big pile of lab reports, Rea would actually look through the entire stack. Several patients have commented on how surprised they were at that, as opposed to the other doctors they’d seen.

He was usually optimistic, telling new patients “I think we may be able to help you,” but not always. This writer met a young woman who grew up in a house where the backyard fence was part of a giant chemical plant in southern Texas. Rea told her she was too damaged to really help, but he could try to make her more comfortable. Such honesty impressed her.

Rea expected the patient to be part of a team to solve the problems – not a piece of meat without a brain, as many other physicians approach their patients. That didn’t mean he suffered fools too easily. Some patients brought their half-baked ideas to Rea, and were frankly told what he thought.

One time he did correct this writer. I had referred to non-organic food as “normal food.” He pointed out that pesticided food was not “normal,” organic food was.

When a patient needed a letter explaining the illness to their employer, landlord or insurance company, Rea would usually help and didn’t charge much for it. He was really there for his patients.

Rea did prescribe drugs, but sparingly and not as the first approach. Many new patients arrived with a slew of prescriptions they had been put on as they went from doctor to doctor. Rea carefully evaluated the list and often started with a plan to eliminate most, if not all of them. They were typically symptom treatments; he wanted to remove the cause of the symptoms instead.

It is hard to know how successful he was. His clinic was where other doctors sent the patients they gave up on, so he saw the most difficult cases. Long-term patients who came back year after year would recognize other patients, so it was easy to wonder how many were actually helped. But there were many more who came for some weeks and never came back – were they helped so they didn’t need to come back, or did they give up? Or did they just run out of money?

This writer originally stayed at the clinic for two months, during which I associated with a group of other new patients who all had severe MCS. Out of those dozen people, three got dramatically better within a couple of months. One was so sick we thought she would die, but after a few years of near-daily treatments, she was amazingly better. Most of the others reported that their health problems stabilized, so at least they stopped getting worse. For all of us, we had at least found a doctor who seemed to understand the problem.

My observation over the years is that most of those who got dramatically better had nearly unlimited funds. They did treatments every day, such as IV nutrients, etc., and kept doing it despite the insurance not covering it.

Special accommodations

The clinic was very good at accommodating people’s special needs. Those who didn’t tolerate the regular (unscented) disinfectants used for skin testing could bring their own. A few people were so sensitive to light that testing room “B” occasionally was kept fully dark, except for one task light kept there for that purpose.

They had a special sauna for those who could not share with other people. If someone didn’t tolerate the towels (washed in Granny’s detergent), they could bring their own.

The staff was amazingly flexible.

Most standard procedures were already as non-toxic as possible. If someone needed oxygen treatment, they were issued a ceramic canula and instructed how to detox the Tygon tubing by gently boiling it. If that was not enough, they offered a stainless steel canula and tubing.

Patient education

Living with severe MCS is complicated. The patients were expected to be a part of the team, and not just pop some pills. The sprawling clinic could also be rather bewildering for a new patient. Education of the patient was an important part of the treatment. This was taken care of by two specialists, who worked there for decades.

Dr. Ron Overberg was the nutritionist, who could interpret the food testing results and help put together a meal plan, among many other things.

Carolyn Gorman was the all-round patient educator, and sometimes advocate too. She could explain what lab results meant, how to make the home less toxic, suggest safer personal care products, and everything else needed to reduce triggers of illness.

Sauna

The EHC-D sauna area

The clinic had a large sauna area with exercise equipment, three saunas, a shower, and a massage room. There was also a separate room used by a changing gallery of physical therapists and other specialists.

The aim was to mobilize and remove chemicals stored in the fatty tissues, which Rea tested for with hair analysis, blood tests, and fat biopsies.

Each patient started with ingesting a cocktail of nutritional supplements. Then used the exercise equipment, followed by a trip to the sauna. From the sauna it was directly into the shower, to wash off the sweat which contained tiny amounts of chemicals. Then ingesting a small amount of tri-salts to lower the acid level again. Finally, a brief lymphatic massage.

The liver was monitored with weekly blood tests, to make sure it was not stressed.

The two larger saunas were fully covered with porcelain tiles. They operated at two different temperatures. The third sauna was a Heavenly Heat model built of poplar and glass. It was used for patients who could not share a sauna with others. Some people simply smelled too strongly of the chemicals they were sweating out that they were a problem for other people with MCS.

Desensitization shots

A mainstay of Dr. Rea’s practice was desensitization shots (antigens) that were tailored to the individual. The vials were made on site in Rea’s own lab, which was one of the few places in the world offering preservative-free allergy shots (conventional allergists use phenol in their shots, which make some people with MCS sick).

The clinic could make custom shots for people who brought samples of dust from their homes, or rented an air sampling machine from the clinic.

Sign on door to testing room B

Testing room B, for the severe cases

As so much else, these shots were controversial among other physicians. Among patients, some saw clear benefits, while others saw none, just as it is for so many conventional treatments. The strength of the shots was tailored to each patient. This was done by recording the size of the wheal it produced on the arm, as well as any symptoms it produced.

The clinic had two testing rooms, a large one for most people, and a smaller one for those unable to be in a room with more regular folks. The smaller room also had a glass room for the most reactive people. It was called “the box.”

IV

Rea did a lot of intravenous (IV) nutrients. The idea was that since the patients were so allergic to things, the digestive system was so stressed it was not able to extract vitamins and minerals so well from the food. The solution was to bypass the digestive system.

Setting up IV bottle

There were some standard IVs, such as the detox cocktail consisting of vitamin C, glutathione, taurine, magnesium, and more.

All the IVs came in glass bottles, instead of the standard soft plastic, which might leach plasticizers, etc.

There were patients who had become so allergic to every possible food that no matter what they ate it made them sick, and their uptake of vital nutrients was very poor. To give their digestive systems complete rest, they were fed intravenously for several months and didn’t eat at all. This was unpleasant and very expensive, but effective. This writer knew two people who did it, and it dramatically helped both of them.

Backlash

No good deed goes unpunished, as they say. Pioneering efforts in science and medicine are no exception. People who challenge entrenched dogma do it at their peril.

The standard example is Dr. Ignaz Semmelweis, who noticed that if physicians washed their hands between patients, far fewer died of infections. This was in 1840 when bacteria had not yet been discovered, so Semmelweis could not explain his observations. But he documented the effect by comparing deaths at two maternity wards, one where the staff practiced good hygiene, the other not. Semmelweis was driven out of town by his enraged colleagues. History is full of similar stories (Davis 2007; Makary 2012; Mirsky 2017).

Rea was foremost a clinician. His priority was to help his patients as best he could, even if he had to use treatments that were not proven by academic studies, but seemed to help at least some patients.

This has been the approach of clinicians for centuries, such as during the tuberculosis epidemic before antibiotics were discovered. More recently, doctors tried to help AIDS patients in the 1980s and early 1990s, before an effective treatment was developed (France 2016).

Academics often criticized Rea and his fellow environmental physicians for using academically unproven treatments, but the alternative was to tell the patients to go home and wait decades until some university might actually study the problem – if they ever got around to it, which they still haven’t. Or drug them to the gills, so they feel nothing, but live like zombies. Many of his patients credit Rea with saving their lives. There are no studies on what the death toll is for people who trusted the critics and did nothing to save themselves.

The critics were especially the allergists whose turf the environmental physicians thoroughly stepped on. In their criticism they conveniently forgot that their own specialty used allergy shots for decades before they were validated by academic studies (Ashford 1998: ch 10).

Many standard medical practices are still done without knowing why. Anesthesia has been used for 170 years, but they still don’t know how it works (Fox 2018).

Prozac has been a blockbuster drug for decades. They thought they knew how it worked, but newer research shows that theory didn’t hold. And the drug only works for 15% of the people it is prescribed for (Economist 2022).

Some critics even accused the environmental physicians of making their patients sicker by believing them, instead of writing them off as psychosomatic. An allergist, whose office was just a block away from Rea’s, commented to a local magazine (Whitley 1990):

I’ve never seen anybody completely debilitated by [MCS]. I have seen people debilitated because they were told they were.

A medical conference was held in Aspen, Colorado, in 1995. Organized by two very outspoken critics of MCS, it had a speaker directly criticizing Dr. Rea’s methods. In a trip report by an attendee representing the big tobacco company Philip Morris, the speaker was quoted calling Rea’s clinic by a totally wrong name: “American Environmental Medical Foundation.” Apparently a mix-up of the name for the store next to Rea’s clinic, this misnomer was also used in other anti-MCS settings at the time (Philip Morris 1995).

Two of Rea’s desensitization shots received special scorn. A journalist went as far as calling them a fraud in a shallow book he wrote about MCS (Broudy 2020).

The shots were labelled “Jet fuel” and “The North Wind.” The concern with “Jet fuel” was whether the patients were actually injected with toxic jet fuel. There was no jet fuel in the vial, it was actually made with an air sampler placed downwind from a busy airport runway. A more accurate label would have been “jet exhaust.”

“The North Wind” came about when a patient observed that she felt sick whenever the wind blew from the north. (This writer actually met this patient.) Presumably, some sort of fume, mold or pollen was carried to her Dallas home from the north.

Using the clinic’s air sampling machine, Rea’s lab made up a shot from whatever the machine picked up. This seems reasonable and not at all sinister, but journalists and others rarely seemed interested in finding out if their “sensation” is really genuine.

The most serious attack on Dr. Rea started in 2005 when the Texas Medical Board investigated him for malpractice (Rea 2007; other sources).

The intent was to revoke Rea’s medical license and discredit his name.

The whole affair smelled very bad. The complaint to the Board was filed anonymously, ostensibly on behalf of five patients treated by Rea. But all five patients were unaware of the complaint ahead of time, and all of them wrote letters to the Board in support of Rea. Two of them even credited Rea for saving their lives.

The Board ignored these letters. They also refused to let Rea’s lawyers inspect the evidence, claiming it was confidential. And they refused to reveal who the anonymous filer of the complaint was, though much later they admitted it was the insurance company United Health Care/Oxford, which insured all five patients.

It is disturbing that an insurance company can use patients’ medical records without their permission.

One of the allegations was that Rea endangered people by injecting them with jet fuel. That was the shot mentioned earlier, which actually was air sampling.

After five years of expensive legal wrangling with a tenacious Board, the allegations were reduced to giving Rea a mild slap on the wrist for not informing his patients about the contents of his shots and that their use was controversial. Anything less would be a complete exoneration, and that would mean the Board would lose face.

All that meant was that the wording of the consent form was changed.

Awards

Rea received many awards, from Temple and Capital Universities, and the Governor of Arizona, to the Mountain Valley Hall of Fame.

Display of Temple University award in 2006

American Environmental Health Foundation

Early on, it became clear that patients had difficulty finding non-toxic household goods. To address the problem Rea created the American Environmental Health Foundation, which operated a little store next to Rea’s clinic.

The Foundation store stocked all sorts of things, from clothes made of organic cotton, to non-toxic detergents, aluminum tape, toothpaste, books, paint, air purifiers, nutritional supplements, and much more.

The Foundation staff organized an annual medical conference, which was held in Dallas each summer from 1982 to 2010.

The profits from the Foundation provided a modest amount of funding for Rea to do research.

Research

Though Rea’s priority was helping his patients in his busy clinic, he was also a prolific writer of scientific articles and books. From 1975 to 2017 he published 121 medical articles and book chapters on a wide range of environmental medicine issues. He also authored ten books, either directed to other physicians or to patients.

He traveled the world giving lectures in Japan, China, Australia, Mexico, all over Europe, and all over North America. He did more than 350 such presentations, mostly to other physicians.

He wrote about his observations, and what he learned from his studies. His studies were pioneering and usually very small; just to see if an observation or idea could hold up to some scrutiny, and to spur interest for larger academic studies – which unfortunately still haven’t happened.

In the years he operated his ECU wards, he often studied patients staying in that controlled environment. That eliminated a lot of “noise” in the data. When the patients do not have to dodge chemical exposures on a daily basis, they both feel better and feel safer, which makes studies on them much better. Unfortunately, no facility like that was ever built for academic studies.

Rea looked at a wide range of topics, such as whether exposures to fumes could alter the heart rhythm, whether people with MCS had slower contraction of their pupils, and whether people with anxieties got calmer in a non-toxic environment. He found all those effects (Rea 1978; Bertschler 1985; Shirakawa 1991).

Together with his lab director, Dr. Bertie Griffiths, he developed a treatment to boost the immune system. Called Autogenous Lymphocytic Factor (ALF), it used the patient’s own white blood cells, which were grown in the lab (Griffiths 1998).

In the early 1980s Rea saw a new patient, a woman from Texas, who reported that her clothing iron bothered her. Most physicians would have either ignored that, or written her off as crazy. But Rea thought about it and wondered if the strong magnetic field could be the cause. This started his interest in electrical hypersensitivity, though he may not have been the first to discover it, as there were also cases in Scandinavia at this time.

A landmark study was published in 1991, where he studied a hundred people who reported electrical sensitivities. An important finding was that it is crucial to screen the test subjects, and that people with electrical sensitivities are sensitized to specific frequencies, but not all. Sadly, this study has never been repeated, and later studies didn’t learn from the methods employed here (Rea 1991).

Three years later Rea did a similar study, but omitted most of the cumbersome screenings and environmental controls to see if such a much simplified study would work (Rea 1994). It did not, but detractors have since used this study to falsely claim it contradicted his own 1991 study.

In the later years Rea had a large Faraday cage – a room where the walls, floor and ceiling were shielded against radio waves with copper mesh. He doesn’t seem to have published any studies using it.

Since environmental physicians often had trouble getting their articles into medical journals, they created their own, which was named Clinical Ecology. It was published from 1982 to 1992 (it was renamed Environmental Medicine the last two years). Rea wrote twenty-two articles for this journal alone. Unfortunately, today’s big online databases do not carry this journal, but most of Rea’s other articles are still available.

Far outside the box

Rea seemed to have a boundless curiosity and was not afraid to consider ideas far outside the box of conventional medicine. Many small experiments were tried to see if an idea showed promise. There doesn’t seem to be any records of these attempts, but some stories circulate.

Some patients were sensitive to sunlight. One of Rea’s experiments was whether he could make a desensitization shot for it. He placed a sealed sterile glass bottle on the roof of the building where it was bathed in sunshine for months. Apparently, the idea was based on homeopathy. Unfortunately, the shots made from the irradiated water did not work. But it was worth a try.

When an alternative practitioner brought in a bag of “energetically potentiated” bentonite clay, Rea doled out samples to some of his long-time patients to try (including this writer). Another dud.

Training other physicians

Rea trained a lot of physicians in his methods. His lectures reached many, and ten physicians apprenticed at his clinic for up to four years. One was Dr. Sherry Rogers, who then opened her own clinic in Syracuse, New York, and went on to write a lot of books on this topic, of which her Tired or Toxic, is a classic.

Another was Dr. Gerald Ross who then spearheaded the creation of an environmental clinic in Halifax, Nova Scotia.

In the early 1980s, dry cleaning fluid leaked into the water supply in Nova Scotia, Canada. This might have been the cause of several people in the area getting MCS around this time.

One of these people were Dr. Gerald Ross, who got sick in 1982. He nearly had to give up his practice. In 1986 he went to Dr. Rea in Dallas, and improved greatly. Seeing first-hand what environmental medicine could do, Ross entered a two-year training program at the Dallas clinic, and also at the Nightingale Hospital in London, England. This was supported financially by the Nova Scotia Department of Health. From 1989 Ross held a staff position at Rea’s clinic for the next decade.

Meanwhile the MCS sufferers in Nova Scotia still had no adequate medical services. The local MCS support group mounted a strong campaign to convince the local health authorities to open an MCS clinic. After years of effort, they were heard.

In September 1990 the Nova Scotia Environmental Medicine Clinic opened at the Victoria General hospital. It was open one month out of every three, with Dr. Ross and technician Betty Bruce each time flying up from Dallas. The local staff consisted of one nurse and one secretary (McDonald 1994).

In 1995 a full-time clinic opened in new quarters at Dalhousie University, with a local staff. The clinic was then self-sufficient without the fly-in staff from the EHC in Dallas.

The Dallas ecosystem

A whole ecosystem emerged around Dr. Rea’s clinic. If you needed a dentist or another medical specialist, Dr. Rea could recommend someone who accepted environmental illness and could take it into account.

It is so much easier to discuss the materials used for filling a cavity with a dentist, or in the implant to cure cataracts with an eye surgeon, if they know those are serious questions for someone with MCS – and they are not just fussy. Or if someone seeks counseling to help with the trauma of losing their family and income because of the illness, it’s a lot easier if the counselor doesn’t think MCS is all a made-up anxiety.

If someone needed surgery, Rea could provide assistance in choosing materials used for implants, such as for cataracts.

The Rea ecosystem included the Abrams-Royal pharmacy, which had daily deliveries to Rea’s clinic. They compounded drugs with minimal fillers and preservatives for the MCS patients. They also made the intravenous concoctions administered to patients in the clinic.

This ecosystem worked well, but wasn’t always perfect. A home health care company that worked with Rea’s patients frequently sent workers who smelled terribly of fragrances or laundry chemicals, and ignored pleas for cleaning up their act.

A number of other businesses catering to people with environmental illness sprung up. They offered high-quality air purifiers, porcelain trailers, cotton masks, ceramic oxygen masks, ozone machines, and much else. An MCS “general store” called the Living Source operated for many years in Waco, south of Dallas.

Rea sometimes ate lunch at a small restaurant in the Deep Ellum neighborhood. The restaurant was known for its excellent bread. One day Rea asked the owner, Francis Simun, if he could make bread without wheat. Eventually Simun’s bakery specialized in making bread out of three dozen different flours, many of which he milled himself.

His bread and bagels were shipped nationwide. Once a day his bagels were delivered to the Foundation store at Rea’s clinic. They arrived warm in time for lunch and were very popular among the patients on restricted diets.

It may be a coincidence, but the first Whole Foods store in Dallas opened just a couple miles east on Walnut Hill (it has since moved).

Many of these medical professionals and business owners were themselves patients of Dr. Rea. Their MCS was mild enough that they could work, and having their own business allowed them to set their own rules regarding smoking and use of fragrances, pesticides, etc. so they could function.

Many patients moved to Texas permanently. That way they were near health care that was friendly to people with MCS, and they could find less-toxic housing. If they wanted to build or convert their own house, specialist help was available there. The local MCS communities also meant an end to social isolation as regular people often refused to stop using toxic personal care products and laundry products. Texas also offered a lower cost of living than many other places.

Some patients settled around the Dallas area, both in the city itself and in the surrounding areas such as Denton and Seagoville. Some settled further away in more pristine air, such as in the Texas Hill Country and western Texas.

Housing

Patients came to the clinic from around the world. Many were too sick to stay at hotels. Some stayed in the environmental units, but that was very expensive and they eventually closed. There was a need for something simpler and cheaper, especially for the patients who moved there permanently.

In 1982 Rea talked to a patient who had bought a large piece of land near Seagoville, southeast of Dallas. The patient agreed to allow another patient to camp there in a camping trailer. That became the start of Ecology Housing, which in the 1990s had about two dozen residents housed in little porcelain huts and campers.

When the original owner died, he deeded the property to Tommie Goodwin, who operated the place until her death in 2022.

Dr. Sprague, who was associated with Dr. Rea, converted a villa in the suburb of Garland and rented out individual bedrooms to the patients.

Ecology Housing in Seagoville

Dr. Rea started buying up condos in a complex on Meadow Lane. They were modified with tiled floors and rented to patients like a hotel.

Eventually many of these apartments became moldy because some people didn’t tolerate the heating system and left it off during the winters. Then a giant powerline was erected on the east end of the complex. The whole complex was sold and demolished. Instead, Rea took over one building at the nearby Marriott Courtyard hotel and converted the suites. But eventually Marriott wanted them back.

A patient and her husband leased an apartment building in the nearby Raintree complex and rented the apartments to people with MCS. Most renters lived there long term. They wanted the rent to be affordable, so the modifications were simple. They just ripped up the carpets and left the concrete floors bare without tiling them. It was very basic, but it worked fairly well.

Around 2001 someone opened a small trailer park on a wooded lot next to Dr. Rea’s ranch by Lake Tawakoni. Here people had to bring their own trailers. But this enterprise operated for just one year.

In 2002 Earl Remmel opened an apartment building off Greenville Road, about three miles south of the clinic. It was extensively renovated. A decade later he also built a dozen rental houses outside Ennis, south of Dallas.

At the time of Rea’s death in 2018, most of these housing projects had closed for various reasons. Only Ecology Housing and Earl Remmel’s two projects were still operating. Most of the other small businesses had closed as the original owners retired or died.

End of an era

Dr. Rea died peacefully at his home on August 18, 2018. He was 83 years old. Dr. Elizabeth Seymour bought the practice. The patient load had slowly declined over the past decade and the clinic had become too big, so Dr. Seymour moved it to a new location in October 2021. It is now at 399 Melrose Drive, suite A, Richardson, TX 75080.

More information

More historical articles about MCS, including one about the environmental control units, are on: www.eiwellspring.org/mcshistory.html

The book Chemical and Electrical Hypersensitivity: A Sufferer’s Memoir (2010) has a detailed account of one of Dr. Rea’s patients, who lived in Dallas for over two years.

Sources

The author was a patient of Dr. William Rea for nearly twenty years and was once a guest at his Tawakoni ranch. All the pictures are by this author.

Several people have provided information used in this article, including Dr. William Rea, Tommie Goodwin, Francis Simun, Ellie Hickey, Betty Bruce, Margaret Tatlock and others who need to remain anonymous. However, any mistakes are the sole responsibility of the author.

A 36-page listing of Rea’s formal education, memberships, awards, speeches, and publications was retrieved from the clinic website. It provided much information used here.

References

Ashford, Nicholas and Claudia Miller. Chemical exposures: low levels and high stakes (second edition), New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1998 (available for free download from University of Texas website).

Bertschler, J. et al. Psychological components of environmental illness: factor analysis of changes during treatment, Clinical Ecology, vol III No 2, 1985.

Broudy, Oliver. The Sensitives: the rise of environmental illness and the search for America’s last pure place, New York: Simon & Schuster, 2020.

Davis, Devra. The secret history of the war on cancer, New York: Basic Books, 2007.

Economist. The need for a clear head, The Economist, October 22, 2022.

Evans, Jerry. Chemical and electrical hypersensitivity: a sufferer’s memoir, McFarland, 2010.

Fox, Douglas. The brain re-imagined, Scientific American, April 2018.

France, David. How to survive a plague, New York: Vintage Books, 2016.

Griffiths, Bertie et al. The role of the T-Lymphocytic cell cycle and an Autogenous Lymphocytic Factor in clinical medicine, Cytobios 93, 1998.

Makary, Marty. Unaccountable: what hospitals won’t tell you and how transparency can revolutionize health care, New York: Bloomsbury, 2012.

McDonald, Cathy. The N.S. Environmental Medicine Clinic: from how it came to be, to the present day, EHANS (Environmental Health Association of Nova Scotia), Fall 1994.

Mirsky, Steve. None so blind: disregarding new scientific information can be deadly (Anti Gravity), Scientific American, February 2017.

Philip Morris. Environmental Medicine Conference in Colorado (internal memo), no author listed, September 15, 1995. Available from PMDocs archive, page 2057342442.

Randolph, Theron and Ralph Moss. An alternative approach to allergies (revised), New York: Harper and Row, 1990.

Rea, William. Environmentally triggered cardiac disease, Annals of Allergy, 40, 1978.

Rea, William et al. Electromagnetic field sensitivity, Journal of Bioelectricity, 1991.

Rea, William. Letter to patients about Texas State Medical Board disciplinary action, September 18, 2007.

Shirakawa, Shinji et al. Evaluation of the autonomic nervous system responses by pupillographical study in the chemically sensitive patient, Environmental Medicine, 8, 4, 1991.

Temple, Truman. On the cutting edge, EPA Journal, October 1980.

Wang, T. Hawkins, L.H., Rea, William. Effects of ELF magnetic fields on patients with chemical sensitivities, Graz conference, 1994.

Whitley, Glenna. Is the 20th century making you sick? D magazine, August 1990.

2024