The war of words against people with multiple chemical sensitivities

In the 1980s and 1990s the medical establishment felt threatened by the new illness MCS, since it contradicted much medical dogma. The response to such heresy was not pretty and frames the debate to this day.

Keywords: chemical sensitivity, environmental illness, environmental sensitivity, MCS, history, hostile, disinformation, physician, resist, paradigm shift

During the 1980s, multiple chemical sensitivities turned out to be more than just an oddity. The media wrote sympathetic stories and hundreds of physicians embraced the new teachings that questioned much dogma. Drugs were accused of being symptom treatment and not actually addressing many illnesses.

The new thinking threatened to revolutionize allergology, psychiatry and toxicology, and make the practice of those specialties much more complex. Such a paradigm shift was not welcomed by many physicians who fought back vehemently against what they considered heresy. The result was a nasty turf war.

As noted in a 1987 medical journal:

Those medical groups that do not accept [environmental medicine] react to it far more intensely than they do to nonphysician alternative health care approaches (Brodsky, 1987).

Dr. Mark Cullen of Yale University remarked the same year:

[There is] an ever widening and hostile debate in which the patient is held hostage (Cullen, 1987: Conclusion).

Two university sociologists commented in a book about this issue:

[B]iomedicine shares with the major social institutions of the era a remarkable capacity to avoid self-examination (Kroll-Smith, 1997 p. 59).

The number of physicians who actively fought against the acceptance of MCS was actually rather small – perhaps just two dozen, many of whom are quoted in this document. But they were very active at medical conferences, in medical journals and other places – and their message had a welcoming audience.

Some of these physicians had financial ties to special interests which dearly wanted MCS to go away. Such ties included lucrative consulting fees from companies sued by people who got sick at work, as well as direct payments (Terr, 1986; API, 1990; Harrison, 1992; Witorsch, 1992; Sparks, 1990; Bandler, 1998).

In an internal briefing paper made by the chemical industry, it was suggested as "absolutely necessary" they work with doctors and medical associations to fight the growing acceptance of MCS, which the industry saw as a threat to their business (Credon, 1990).

It was somewhat common at this time that corporations secretly paid physicians to write letters and editorials that defended controversial products, such as tobacco (Angell, 2000; Kaiser, 1998; Brennan, 1994; Smith, 2006; Greene, 2017).

Whether there were such direct letters-for-hire schemes used against MCS is unknown, though some of the prolific writers did receive money from industries with a strong interest in discrediting MCS (Harrison, 1992; Witorsch, 1992).

One bone of contention was that the renegade physicians used the new paradigm to experiment with a wide variety of treatments. They were clinicians and not academics; their first duty was to help their patients as best they could.

They started to use treatments that seemed to be helpful though they were not verified by academic studies. This greatly hurt their respectability, but it was a vicious circle as there was no funding available to do proper studies, as funding was blocked by the old guard's resistance (Miller, 1994; Ashford, 1998; Meggs, 2017).

In this tense atmosphere, there was a lot of sniping in the medical journals, such as:

The variety of treatments seemed to be limited only by the imagination and resourcefulness of the clinician (Black, 1990b).

Dr. Black was a psychiatrist, but some allergists were as eager in their comments. This despite their hypocrisy, as allergists themselves used allergy injections for decades before they were validated by science (Ashford 1998: ch 10).

The allergist Dr. Abba Terr reported for 50 MCS patients who had already been to environmental physicians:

Treatment ... failed in every case to produce a remission... (Terr, 1986).

Of course, it would be surprising if the treatments worked and the MCS patients still came to Dr. Terr. Forty-six of the fifty people were sent by insurance companies, etc, precisely because they were applying for disability payments. Patients who were cured would not seek compensation. Only four of the patients came to Dr. Terr on their own accord.

Despite the obvious bias, this conclusion was echoed in other anti-MCS medical articles (Black, 1990b, 2001).

Terr was well known in the patient community for his dismissal of MCS as a legitimate illness, presumably that was why insurance companies liked to send claimants to him for evaluation and why the MCS patients rarely came voluntarily.

Dr. Terr's report was then further twisted as "proof" that people with MCS were just looking for money:

Some, especially among the patients, certainly have an eye on litigation. Terr's systematic examination of fifty consecutive patients referred for reevaluation for a clinical ecology [MCS] diagnosis found that forty-three were pressing worker's compensation claims and two others were pursuing tort claims against chemical manufacturers. Only five, apparently, had no specific financial interest in being sick... (Huber 1991 p. 107).

This is a clear example of manipulation of the reader by very selective use of statistics. It was not made clear that Terr almost exclusively saw patients sent to him by insurance companies, thus the high number of people seeking compensation. This was published in a highly polemical book that railed against any kind of "junk science" that threatened corporate interests. It was written by a non-physician.

Physicians practicing environmental medicine often got into the field because they had the illness themselves, or knew someone who did. This is twisted into a sinister fact:

Ecologists claim a unique identity with victims of the environment by declaring themselves, or members of their families, similarly affected. In the author’s opinion, this is a powerful bonding tool which snares patients into a familiar cult interdependence in which facts are irrelevant (Selner, 1986).

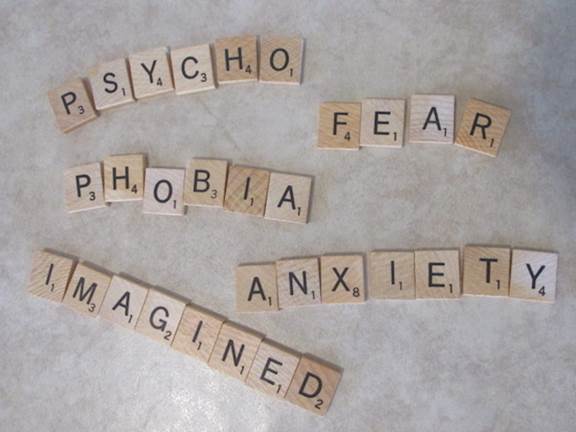

Some detractors even went so far as to accuse the environmental physicians of making their patients sicker by believing them. In the following five quotes, these physicians all use psych terms (“invalidism,” “belief,” “phobia,” “fear”) to suggest the sick people should be sent to a psychiatrist instead of an environmental physician:

Clinical ecology lacks scientific validation, and the practice of "environmental medicine" cannot be considered harmless. Severe constraints are placed on patients' lives, and, in many cases, invalidism is reinforced as patients develop increasing iatrogenic [doctor caused] disability (Kahn, 1989).

... until a clinical ecologist [environmental physician] diagnosed environmental illness. Thereafter, fear of chemicals led to symptoms (Terr, 1986).

It follows then that environmental illness is not a disease or syndrome, but rather it is a belief that illness must be present if an environmental exposure has occurred (Terr, 1987).

Clinical ecology methods, however, may expand appropriate concerns about chemicals to nonspecific fears, resulting in iatrogenic [doctor caused] phobia. We ... propose the term "toxic agoraphobia" to describe the phenomenon (Kurt, 1990).

At its worst, such unsubstantiated postulation harbors iatrogenic [doctor caused] exploitation and beliefs of victimization (Staudenmayer, 1997).

The psychiatrist Dr. Donald Black told a San Diego newspaper that:

They plant the notion of environmental illness in their patients' heads (McIntyre, 1992).

An allergist in Dallas, Texas stated to a local magazine:

I've never seen anybody completely debilitated by [MCS]. I have seen people debilitated because they were told they were (Whitley, 1990).

The president of National Medical Advisory Services, an organization assisting businesses sued by employees who got sick with MCS on the job, wrote:

This is a phenomenon in which the diagnosis is far more disabling than the symptoms (Gots, 1995).

This idea was also promoted in a sponsored article that was published in more than a thousand newspapers. It stated:

[MCS] exists only because a patient believes it does and because a doctor validates that belief.

The article was sponsored by the industry front group Environmental Sensitivities Research Institute – ESRI (Ashford, 1998: ch 9).

Some of the environmental physicians testified in court on behalf of the patients. A book focused on ridiculing court cases where people have been injured by corporations had a chapter about MCS. It is a strongly worded book. About these physicians it says:

[The] clinical ecologist [environmental physician] is an outlier, an aberration, a living example of dysfunction and pathology... He has experience with persuading, for his clinical practice depends entirely on persuading patients first that they are sick, then that they have been cured (Huber 1991).

A well-known opponent of alternative medicine wrote a booklet titled "Unproven 'allergies': an epidemic of nonsense" where he railed against environmental physicians, ending with the statement (Barrett, 1993):

I believe that most of them deserve to be delicensed.

The booklet was published by the American Council on Science and Health (ACSH), which Consumer Reports (1994) said had strong financial ties to the chemical industry and had argued in favor of several controversial chemical products manufactured by the funders of the organization.

Physicians became afraid of even suggesting to their patients that they avoid the chemicals that made them sick, since they feared being disciplined by their medical boards. Some physicians had to fight costly legal battles to keep their licenses (Hileman, 1991; Nelson, 1994; Lipson, 2004; Meggs, 2017).

It was much like the classical story about the physician Ignaz Semmelweis, who in the 1840s discovered that if physicians washed their hands between seeing each patient, there were a lot fewer deaths from infectious diseases. Bacteria had not yet been discovered and Semmelweis could not explain his discovery, though the statistical tally he kept comparing the deaths at two maternity wards was clear. He was driven out of town by his incensed colleagues (Wikipedia).

Attacking whoever brings unwanted health findings has happened many times since. This includes against scientists who found air pollution from factories and cars killed people and that various chemicals could cause birth effects, infertility, cancer and more. Even the epidemiologist Alice Stewart, who discovered that x-rays are harmful to human fetuses. Or Harvard physician Ernest Codman, who wanted his colleagues to keep track of their mistakes and learn from them. They have been subjected to denied tenure, firing, accusations of fraud, cancelled funding and much else (Davis, 2002: ch 3-5, 9-10; Greene, 2017; Makary, 2012).

Attacking the sick

The wrath of the old guard was not limited to MCS-treating physicians. The MCS patients were also the target of their derision in both newspapers and medical journals.

When the federal government built a small apartment building in California to house people with MCS, there was no end to the mockery. In an editorial in the Journal of Clinical Immunology, one could read:

"Ecology House" ... serves only to further exacerbate their feelings of victimization and displaced anger (Staudenmayer, 1997).

On the television station KGO in San Francisco, a physician stated:

[T]he project perpetuates a notion that the syndrome has a physical cause (New Reactor, 1994).

The Cleveland Plain Dealer sent a journalist to look at the nearly finished building. The article was sharply critical of the project and quoted five physicians who were opposed to accepting MCS as a legitimate disease. Here are quotes from those five physicians (Epstein, 1994):

[Many] believe they are allergic to everything in order to avoid confronting a painful life experience (Dr. Selner).

[MCS is] a name in search of a disease (Dr. Witorsch).

It's a culturally acquired anxiety disorder without known cause (Dr. Johnson).

It's an unproven condition we don't see much evidence for (Dr. Estes).

[MCS is] primarily a psychophysiological response to a perceived threat (Dr. Horvath).

These sentiments were echoed by other physicians, such as when Dr. Gots created the ESRI organization to fight the growing acceptance of MCS:

The phenomenon of multiple chemical sensitivities is a peculiar manifestation of our technophobic and chemophobic society (Gots, 1995; Risk Policy Report, 1995).

And also:

It appeals to the widespread fear of chemicals; the distrust of science, medicine, technology, and government; environmental worries; and the American mindset of victimization (Gots, 1995).

Similar sweeping statements were made by other physicians, most of whom we've already quoted in this article:

As defined and presented by its proponents, multiple chemical sensitivities constitutes a belief and not a disease (Terr, 1987).

It's a belief, not a disease. .... It's a culturally acquired anxiety disorder, without known cause (Wilson, 1994).

Dr. Donald Black was one of the most opinionated voices:

In recent years, this "total environmental allergy syndrome" has become faddish (Black, 1990a).

EI beliefs may be interpreted as "odd" or "magical" (schizotypal personality), may lead to a focus on the "special nature of one's problems" (narcissistic personality), or its treatment may lead to "avoiding social or occupational activities" (avoidant personality) (Black, 1993).

... their illness has developed into a useful coping strategy because they are now able to attribute their various stresses and problems to EI [environmental illness], as if to imply that if it were not for EI their social, marital and job-related problems would vanish (Black, 1993).

Dr. Black stated to the New York Times:

It's my belief that people diagnosed as having environmental illness in most cases do have something wrong: a garden variety emotional disorder (NYT, 1990).

When the media got interested in the MCS community near Wimberley in rural Texas, Dr. Black provided them with his opinions:

Major mental disorder (Hall, 1993).

These are ill people. But I don’t believe they have what they think they have (McIntyre, 1992).

Other outspoken psychiatrists wrote:

... withdrawal from work, a life-style engineered to avoid exposure to putative noxious substances, and an identity as a disabled person (Brodsky, 1983).

At some level, the person recognizes that his relationship to his surroundings is not as comfortable as he would like, and rather than accept an internal cause, he adopts a model wherein he can fix blame on the hostile, toxic environment – in the past the diagnosis might have been neurasthenia or hysteria (Brodsky, 1989).

... a belief characterized by an overvalued idea ... similar to anxiety, specifically panic disorder ... a cognitively mediated fear response ... amplified in the process of learned sensitivity (Staudenmayer, 2003).

Some psychiatrists suggest people with MCS are sick because they want to receive “secondary gains:”

The ‘illness’ stabilizes social relationships, it allows withdrawal from unbearable strains and guarantees personal and professional care (Bornschein, 2001).

Or stress and fear of modern life:

The complex problems of these persons are compounded by the fact that their multisystem complaints are often attributable to the cumulative effects of stress and fear of future development of disease resulting from exposure to chemicals, additives, and antigens in the environment (Salvaggio, 1994).

Another psychiatrist suggests the disease is caused by:

the restructuring of women’s roles during recent years has increased their tendency to stress- and fatigue-related disorders…She is relieved of overwhelming demands from home, family, and job, and others must now take care of her (Brodsky, 1989).

These statements demonstrate how far removed from the realities of MCS these physicians are. MCS often results in break-up of families, with the sick person left to fend alone, the exact opposite of what these two psychiatrists claim.

They also resort to stereotyping (Brodsky, 1989):

[M]ost commonly the patient is a woman between 30 and 50 who is intelligent and educated. Typically, she is married, has children, and worked prior to becoming ‘disabled.’

The above statement was made with no scientific basis. Later studies showed that people of all educational levels and backgrounds get MCS.

Sick building syndrome appears to be a form of MCS. When there were reports of several sick buildings in Tampa, Florida, a director at the local medical school blamed it on media hysteria. He also stated:

There is no scientific evidence whatsoever that this syndrome even exists ... The majority of these people, we think, have other kinds of problems (Fechter, 1992).

Dr. Staudenmayer stated to the Boston Globe:

No matter what you do to the 'sick' building, it will not meet the demands of the afflicted. Nothing is ever enough (Bandler, 1998).

There was a lot of experimentation in the 1980s and 1990s to find out how to create healthy buildings. Many of the early projects were half-hearted or misguided and not initially successful. Today, well-built healthy buildings have a high success rate. Unfortunately, some projects falter because they are not monitored well in the construction phase.

The detractors were very active at convincing other physicians that MCS is all psychosomatic. They did that at various medical conferences. Since these are verbal presentations, we have few actual quotes available. A trip report written by a tobacco company employee about a 1992 medical symposium quotes Dr. Staudenmayer as saying the MCS patients have a:

morbid absorption with bodily functions with the illness being the center of their life (Logue, 1992)

Some detractors paint the environmental illness movement as almost a religious cult:

The medical anthropologist can study the professionals, the leaders, the priestly members of the society, as well as those who approach it to be admitted, those who go through the rites of passages, those who are accepted or rejected (Brodsky, 1987).

That it constitutes a movement rather than merely a new medical theory seems obvious. ... Not surprisingly, some people are receptive to the rhetoric of a group that claims to show how harmful environmental chemicals can be, not just as potential carcinogens or mutagens but as agents of immediate disabling illness... (Kahn, 1989).

This subculture seems to appeal to patients with a history of chronic psychiatric symptoms ... (Brodsky, 1983).

Despite the significant therapeutic effort expended, some patients who are imprisoned by a closed belief system about the harmful effects of chemical sensitivities are resigned to travel down the path which ultimately leads to despair and depression, social isolation, and even death (Staudenmayer, 1996).

Even the most ardent opponents of accepting MCS as a legitimate disease occasionally admit that MCS doesn't fit neatly into any psychological label:

The only unifying psychologic factor among these patients is their overvalued idea that factors in the physical environment are the source of their misery (Staudenmayer, 1997).

Blaming the media

Another favorite is to blame the media, as if seeing MCS on television makes people sick – but what about the many patients who'd never heard about MCS before they got sick?

Over half the households in Manhattan contain one person only. When people in such households arise in the morning they have often only the television with which they can discuss the meaning of puzzling physical sensations. And it will assure them they have chronic fatigue syndrome or multiple chemical sensitivity (Shorter, 1997).

Thus the media have staged a psychocircus of suggestion around MCS, all the while featuring such sister diagnoses as sick building syndrome and Gulf War syndrome in the circus's other rings (Shorter, 1997).

A historian wrote a whole book on this topic, accusing chronic fatigue, Gulf War syndrome and other poorly understood illnesses to be caused by the media:

[P]atients learn about diseases from the media, unconsciously develop the symptoms, and then attract media attention in an endless cycle (Showalter, 1997).

In reality lots of people got sick before they heard these diseases existed.

Since these detractors often believed MCS was a result of media hype, it was popular to promote the idea that MCS existed in just a few countries:

[The MCS] phenomenon is culturally restricted to North America and Europe ... (Staudenmayer, 1997).

One of the most striking facts is that IEI/MCS occurs only to certain societies and countries (i.e. Western industrialized countries)…(Bornschein, 2001).

MCS has since been documented in such diverse cultures as South Korea, Japan, Australia, Uruguay, Brazil, Greenland and elsewhere. They just didn’t look before.

Blaming the victim

The most effective treatment for MCS is avoiding the chemical triggers. This makes perfect sense, but still receives scorn:

As Brodsky observed, these patients develop a lifestyle organized around their illness (Black, 1990b).

The day Donald Black published his small and biased study on the mental health of people with MCS, he said to the New York Times:

Patients become fanatical about their diagnosis – Their whole life revolves around the illness, some of them rebuilding their homes according to environmentally ‘acceptable’ standards, or moving from one part of the country to another (NYT, 1990).

Some even discourage avoiding the triggers:

[T]he physician should discourage the patient from avoiding exposure to wide ranges of substances and conditions present in the normal indoor or outdoor environment that severely limit that patient’s functioning and induce more fear and apprehension (Salvaggio, 1994).

“Deprogramming” is the answer!

Instead, a psychiatrist claimed that MCS could be "deprogrammed":

We have found that patients receptive to an explanation for a disease other than environmental illness can be deprogrammed from ecologic belief and return to functional status 50 to 75 percent of the time. Success depends on the extent to which this belief is rooted in essential primary gain that requires the belief in order to avoid confrontation with painful life experiences (Selner, 1988).

Apparently, in Dr. Selner's opinion, if his "deprogramming" is not working, it is the fault of the patient. Blame the victim. Dr. Selner never published a research article about his "deprogramming" experiments. How many did he actually do? How long did the effect last? He says 50 to 75% of "receptive" patients can be deprogrammed, how many patients did he consider "receptive"?

If his method really was so affective how come there is no "Selner Protocol" treatment that survived the test of time? The people Dr. Selner claimed to cure all sought help from his psychiatric practice. Were they really representative of the general MCS population?

MCS has been documented to exist since at least the 1950s, but some of these commentators seem to believe it will soon go away by itself:

Both parties [physicians and patients] bravely play out this psychodrama until the scientific evidence finally becomes overwhelming that the pseudodisease does not in fact exist, and only then do they move on to the next pseudodisease (Shorter, 1997).

This is even contradicted by one of the other vocal opponents of MCS, who followed a group of patients and found they all still had MCS nine years later (Black, 2000).

Some of these psychiatrists are upset that they can't convince MCS patients that it is an imagined illness, in their opinion:

However, none of these physicians were able to persuade the subjects their diagnosis of MCS or chemical sensitivity was incorrect. The persistence of their beliefs is a feature of people who receive a diagnosis of MCS... (Black, 1996).

It is not surprising these attempts fail at persuading people with MCS that they do not have MCS. It is like trying to persuade people that an ordinary grey elephant is actually pink.

People with MCS usually have to try several physicians to find one who is willing to try to help and not just brush off a hopeless case. The detractors consider this "doctor shopping," which to them is what hypochondriacs do:

... the individual has ended up in that office because of doctor shopping (eg. a somatizer) (Black, 1993).

The same physician also frowned upon the patients becoming dissatisfied with orthodox medicine:

Almost all subjects reported a dissatisfaction with traditional medical practitioners. They believed they were mistreated or mislead by the medical community ... Many felt they had been made to feel like "psychiatric cases" (Black, 1990b).

With little or no help from traditional physicians, people with MCS often seek alternatives. Many of these are very questionable. When Dr. Black interviewed 18 people with MCS, he provided only details of one of them. He extensively described her implausible beliefs regarding pendulums and other things, while not at all stating whether such beliefs were shared by the other 17 people – presumably not (Black, 2001).

When the state of New Mexico wanted to study MCS, the study was opposed by the industry front group TASSC (The Advancement of Sound Science Coalition), represented by one of the vocal opponents:

It is a dangerous model that could mushroom into larger problems for our society ... and even for the victims who may never know the real source of their symptoms (Carruthers and Staudenmayer, 1996).

The TASSC group is better known for defending tobacco from regulation (Michaels, 2008).

Veterans returning from the 1990-1991 Gulf War sometimes became sick with what resembled MCS. Even they were insulted with psychological labels:

The suffering of Gulf War Syndrome is real by any measure, and the symptoms caused by war neurosis are just as painful and incapacitating as if they were caused by Iraqi chemical weapons, parasites or smoke (Showalter, 1996).

Lyme disease was in the early 1990s much less accepted than it is today, and sometimes compared to MCS:

A market for somatic labels exists in the large pool of "stressed-out" or somaticizing patients who seek to disguise an emotional complaint or to "upgrade" their diagnosis from a nebulous one to a legitimate disease. In previous years, sudden increases in diagnostic labels not otherwise justified by epidemiological evidence have included hypoglycemia, total allergy syndrome [MCS], and chronic Epstein-Barr virus infection. Today it is Lyme disease (Aronowitz, 1991).

In a 1997 book, two academic sociologists sum up their observation of the ongoing dispute:

At this moment the dispute is little more than a skirmish of words waged between outlying detachments of opposing forces. The chemically reactive on one side, armed with their somatic experiences, borrowed biomedical interpretations, and a profound determination, look across "no-man's-land" of the profession of biomedicine, armed with the authority of science and the state to control the definition of disease and pronounce bodies sick or well. Each side is supported by important confederates (Kroll-Smith, 1997: ch 2).

After year 2000

MCS became much less of a fight after the year 2000. The medical journals published fewer articles and the media ignored it. There were suddenly fewer of the mean statements.

The indignant voices of the old guard became silent. They didn't retire or die, as searches on the internet reveal. It just seems that they had won the battle. In the first decade of the new century most people falsely believed MCS was a mental disease.

With this belief dominating, it became impossible to get funding for scientific research (Meggs, 2017; Hu, 2018).

The last major medical conference on MCS was held in 2001 (Hu, 2018).

With no medical research and the activists demoralized, the debate calmed down – for now. There are just some quips now and then.

In 2011 a spokesperson for the Monell Chemical Senses Center called fragrance sensitivities "anxieties" and stated that:

[H]ealth care professionals themselves can over-sensitize patients into believing they will have a reaction to fragranced material ... (CMAJ, 2011).

The center claims on their website that they are "independent," but also admits that they have over fifty corporate sponsors from the food, beverage, fragrance, pharmaceutical and chemical industries (Monell, 2020).

Why such a nasty war?

Revolutions are rarely welcomed by the establishment, and that includes the scientific establishment as well. In his classic book The structure of scientific revolutions, Thomas Kuhn describes how scientists can be as resistant to change as everybody else. Many scientific revolutions have already happened, spearheaded by people like Copernicus, Newton, Einstein, Lavoisier, Rontgen and Darwin. All of them faced unyielding resistance as well.

The German Nobel laureate Max Planck wrote:

A new scientific truth does not triumph by convincing its opponents and making them see the light, but rather because its opponents eventually die and a new generation grows up that is familiar with it.

Thomas Kuhn discusses these issues at great length. Some of his insights can be boiled down to that a new paradigm must be seen as progress, it must solve some problems the old paradigm cannot, and it must not undermine too many established "truths."

Accepting MCS as a legitimate illness is a major paradigm shift that attacks many established beliefs, especially the fundamental function of many physicians who dole out a pill after a brief interview. Since there are no drugs that treat MCS (other than ineffective symptom treatment) and people with MCS often have problems tolerating drugs, they are not very useful. Instead, a physician would need to spend much more time helping the patient live a less toxic lifestyle, a task that is much more complex and poorly paid than pushing the pills.

To physicians practicing allergology, psychology, psychiatry, and possibly toxicology, accepting MCS kills too many holy cows and makes their medical practices much more complicated. It is no surprise they are so resistant.

Some have raised very legitimate skepticism about the treatments used on MCS patients, since they have been poorly validated. But as Thomas Kuhn points out, no new paradigm ever arrives fully formed with everything sorted out. Those things can be studied later when funding becomes available. Funding is rarely available before a paradigm is accepted, he says.

As Kuhn says: “the two groups of scientists see different things when they look from the same point in the same direction.” When they look at patients with MCS, the allergists see people who seem irrationally afraid of trivial chemicals. The environmental physicians see people whose bodies react to chemicals at much lower levels than healthy people’s do.

More information

More articles about the history of MCS are available on www.eiwellspring.org/history.html.

2021, updated 2024

References

Angell, Marcia. Is academic medicine for sale?, New England Journal of Medicine, May 18, 2000.

API (American Petroleum Institute). Perspective on Environmental Illness: an industry forum (meeting invitation with list of speakers), 1990.

Aronowitz, Robert A. Lyme disease: the social construction of a new disease and its social consequences, The Millbank Quarterly, 69, No 1, 1991.

Ashford, Nicholas and Claudia Miller. Chemical exposures: low levels and high stakes (second edition), New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1998.

Bandler, James. Clean living, Boston Globe, October 4, 1998.

Barrett, Stephen. Unproven "Allergies": an epidemic of nonsense, American Council on Science and Health, 1993.

Black, Donald W. and Ann Rathe (1990a). Total environmental allergy: 20th century disease or deception, Resident and Staff Physician, March 1990.

Black, Donald, Ann Rathe and Rose Goldstein (1990b). Environmental illness – a controlled study of 26 subjects with '20th century disease,' Journal of the American Medical Association, December 26, 1990.

Black, Donald, Ann Rathe and Rose Goldstein. Measures of distress in 26 "environmentally ill" subjects, Psychosomatics, March-April 1993.

Black, Donald. Iatrogenic (physician-induced) hypochondriasis – four patient examples of "chemical sensitivity, " Psychosomatics, July-August 1996.

Black, Donald, C. Okiishi and S. Schlosser. A nine-year follow-up of people diagnosed with multiple chemical sensitivities, Psychosomatics, May-June 2000.

Black, Donald, Christopher Okiishi and Steven Schosser. The Iowa follow-up of chemically sensitive persons, in: The role of neural plasticity in chemical intolerance, Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, Barbara Song and Iris Bell, editors, 2001.

Bornschein, Forst and Zilker. Idiopathic environmental intolerances (formerly multiple chemical sensitivity) psychiatric perspectives, Journal of Internal Medicine, 2001.

Brennan, Troyen. Buying editorials, New England Journal of Medicine, September 8, 1994.

Brodsky, Carol. Allergic to everything: a medical subculture, Psychosomatics, 24, 731-742, 1983.

Brodsky, Carol. Multiple chemical sensitivities and other "environmental illness": a psychiatrist’s view, Occupational Medicine: state of the art reviews 2, October-December, 1987 (edited by Mark Cullen).

Brodsky, Carroll et al. Environmental illness: does it exist? Patient Care, November 15, 1989.

Carruthers, Garrey and Herman Staudenmayer. Analyze syndrome before making policy (op-ed), Albuquerque Journal, July 6, 1996.

Consumer Reports. The ACSH: forefront of science, or just a front? Consumer Reports, May 1994.

CMAJ. Scent-free policies generally unjustified, Canadian Medical Association Journal, April 5, 2011.

Credon, Karen. "Environmental illness" briefing paper, Chemical Manufacturers Association, 1990.

Davis, Devra. When smoke ran like water: tales of environmental deception and the battle against pollution, New York: Basic Books, 2002.

Epstein, Keith. $1.8 million buys 11 units for 'sensitive' Californians, Cleveland Plain Dealer, July 10, 1994 (front page).

Fechter, Michael. Researchers disagree on 'syndrome': sick buildings don't exist, skeptics say, The Tampa Tribune, November 30, 1992 (front page).

Greene, Gayle. A tale of two scientists: Doctor Alice Stewart and Sir Richard Doll, Corporate ties that bind: an examination of corporate manipulation and vested interest in public health, Martin J. Walker (editor), New York: Skyhorse Publishing, 2017.

Gots, Ronald E. Multiple chemical sensitivities – public policy, Clinical Toxicology, 33, 1995.

Hall, Stephen. People live in houses with aluminum foil, wear gas masks in public, and shun newspapers, deodorant, and most things manmade. They’re crazy right? Or maybe they’re allergic to the 20th century, Health, May/June 1993.

Harrison. November 1992 Activities (report sent to R. J. Reynolds tobacco company), E. Bruce Harrison Company, December 10, 1992. (Document 51142 0996, RJ0186LAZ, industrydocumentslibrary at UCSF.)

Huber, Peter. Galileo's revenge: junk science in the courtroom, New York: Basic Books, 1991.

Hu, Howard and Cornelia Baines. Recent insights into 3 underrecognized conditions, Canadian Family Physician, June 2018.

Kahn, Ephraim and Gideon Letz. Clinical ecology: environmental medicine or unsubstantiated theory? Annals of Internal Medicine, 111, July 15, 1989.

Kaiser, Jocelyn. Tobacco consultants find letters lucrative, Science, August 14, 1998.

Kroll-Smith, Steve and H. Hugh Floyd. Bodies in protest: environmental illness and the struggle over medical knowledge, New York: New York University Press, 1997.

Kuhn, Thomas S. The structure of scientific revolutions (fourth edition), University of Chicago Press, 2012.

Kurt, Thomas L. and Timothy J. Sullivan. Toxic Agoraphobia (letters to editor), Annals of Internal Medicine 112, February 1990.

Lipson, Juliene. Multiple chemical sensitivities: stigma and social experiences, Medical Anthropology Quarterly, 18, 200-213, issue 2, 2004.

Logue, Mayada. Trip report: symposium on Multiple Chemical Sensitivities, Philip Morris inter-office correspondence, November 4, 1992. (PMDocs archive 2024199241.)

Makary, Marty. Unaccountable, New York: Bloomsbury, 2012.

McIntyre, Mike. Canaries in a coal mine, San Diego Union, January 5, 1992.

Meggs, William. History of the rise and fall of environmental medicine in the United States, Ecopsychology 9, June 2017.

Michaels, David. Doubt is their product, New York: Oxford University Press, 2008.

Monell. Monell Center website section for "Support & Sponsorship", accessed January 2020.

Nelson, Eric. The MCS debate: a medical streetfight, Washington Free Press, February-March 1994.

New Reactor. Dr. Dean: Still shooting fish in a barrel, The New Reactor, July/August 1994.

NYT (New York Times). Environmental illnesses disputed condition's symptoms are probably mental disorders, researchers say, New York Times, December 26, 1990.

Risk Policy Report. New multiple chemical sensitivities research group formed, Risk Policy Report, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, June 16, 1995.

Salvaggio, John. Psychological aspects of “environmental illness,” “multiple chemical sensitivity,” and building-related illness, Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, August 1994.

Selner, John and Herman Staudenmayer. The relationship of the environment and food to allergic and psychiatric illness. In Psychobiological aspects of allergic disorders, edited by Young, Rubin and Daman, New York: Praeger, 1986.

Selner, John C. Chemical sensitivity, Current Therapy in Allergy, Immunology and Rheumatology, 3, 1988.

Shorter, Edward. Multiple chemical sensitivity: pseudoscience in historical perspective, Scandinavian Journal of Work and Environmental Health, 23, supp. 3, 35-42, 1997.

Showalter, Elaine. Epidemics of misunderstanding: Gulf vets suffer from shock of war, not gas, The Washington Post, December 15, 1996.

Showalter, Elaine. Hystories: hysterical epidemics and modern media, Columbia University Press, 1997. Chapter 1.

Smith, Richard. Conflicts of interest: how money clouds objectivity, Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 99, June 2006.

Staudenmayer, Herman. Clinical consequences of the EI/MCS "diagnosis": two paths, Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology, 24, S96-S110, August 1996.

Staudenmayer, Herman, Karen Binkley, Arthur Leznoff et al. Idiopathic Environmental Intolerance (part 2), Toxicological Reviews, 22, 247-261, 2003.

Staudenmayer, Herman. Multiple chemical sensitivities or idiopathic environmental intolerances: psychophysiologic foundation of knowledge for a psychogenic explanation (editorial). Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 99, 434-437, 1997.

Terr, Abba. Environmental illness, a clinical review of 50 cases, Archives of Internal Medicine, 146, January 1986.

Terr, Abba. "Multiple chemical sensitivities:" immunologic critique of clinical ecology theories and practice, Occupational Medicine: State of the Art Reviews, vol 2, No 4, October-December 1987.

Witorsch, Philip. Letter to Robert Flaak, Assistant Staff Director, U.S. EPA Science Advisory Board, July 8, 1992. Disclosure that he is a paid consultant to the Tobacco Institute (PMDocs.com 2025797173).

Whitley, Glenna. Is the 20th century making you sick? D Magazine, August 1990.

Wilson, Duff. Crippling illness or just hysteria? – It ruined my life says one sufferer, a doctor, Seattle Times, January 5, 1994.