The campaign to discredit MCS

Around 1990 there was a lot of sympathy for people with MCS in the media and in Congress. The chemical industry in the United States got really concerned over how MCS could impact them and decided to act. Within a few years people with MCS became widely regarded as psychiatric cases instead of having a legitimate illness.

Keywords: MCS, chemical sensitivity, environmental illness, history, opposition, chemical industry, disinformation, environmental illness briefing paper

The gathering storm

Multiple chemical sensitivity (MCS) was mostly known as environmental illness around 1990 when it gathered a lot of interest. More than a hundred employees were sickened when the EPA installed new carpeting at their Washington, D.C. headquarters in 1987 and 1988. Some went on permanent disability (Toufexis 1988; Svoboda 1997).

A store customer had to be hospitalized for ten days after an employee sprayed her with a fragrance (Wolff 1989; LA Times 1989).

There were complaints and lawsuits from employees working with toxic chemicals, such as at the aircraft manufacturer Boeing, and at Silicon Valley chip factories (Sparks 1990; Hembree 1986; Goad 1990; Sanger 1984).

The occupational medicine specialist Mark Cullen edited the 1987 book Workers with Multiple Chemical Sensitivities, which created the term MCS and provided the first working definition.

The professors Nicholas Ashford and Claudia Miller prepared a 1989 report on MCS for the New Jersey State Department of Health (the duo soon after published the landmark book Chemical Exposures: low levels – high stakes).

In 1990 several major newspapers published large and sympathetic stories about people with MCS, both in California (Busico; Minton; Morris; Smith; Wallace; Wysham, all 1990), in the Chicago Tribune (Litweiler; Givhan; Seigel, 1990), in the New York Times (Belkin; Reinhold, 1990), and elsewhere (Champagne; Huckabee, 1990).

The television program Bad Chemistry aired in December 1990 on the TV station KQED in San Francisco (and possibly other PBS stations). It interviewed several physicians, including the outspoken MCS opponent Abba Terr, but was clearly sympathetic to the sick people.

The following year, MCS activists were featured on the major television shows Geraldo Rivera and MacNeil-Lehrer (MBD 1991; Reactor 1991). The Oprah Winfrey show invited the manager of an MCS camp in Texas, but she declined since it was a lot of travel and the show could not accommodate her physical needs (Goodwin 2002).

MCS activists were actively demanding recognition and civil rights (Perlman 1990; MBD 1991; Weidenfeller 1992; Hileman 1991). They were slowly gaining ground.

The federal agency Housing and Urban Development officially recognized MCS as a disability requiring "reasonable accommodation" (Mansfield 1991; Weidenfeller 1992; Hileman 1991).

A boy testified before a U.S. Congress committee that pesticides gave him MCS (HE; Seigel; E mag, 1990).

The Senate voted to pass the Indoor Air Quality Act, but it never got through the House of Representatives. If it had become law, it would have legitimized MCS as a finding (Risotto; Hileman 1990).

The Americans with Disabilities Act gave civil rights to the disabled. When it was signed into law by President George H.W. Bush, three representatives of the MCS community were present as invited guests at the outdoor ceremony (Davis 1990).

The National Academy of Sciences held a two-day meeting on MCS in early 1992, where all viewpoints were represented (NRC 1992). An industry flack noted that of the 45 assembled scientists, about 90% thought MCS was a real physiological disease and not a psychological problem (Holm 1992).

The chemical industry was used to problems around their factories, so they placed them in areas where people were poor and politicians could be bought. Now the complaints were about the products themselves and the complainers were often highly educated.

The CMA briefing paper

The main organization promoting the interests of the chemical industry was the Chemical Manufacturers Association (they later changed the name to the American Chemistry Council).

In 1990 the Chemical Manufacturers Association produced the “Environmental Illness” Briefing Paper. It was intended for their members only, but a copy was leaked to the MCS community (Credon 1990; Reactor 1990).

The paper laid out the threat that MCS posed to their members and to a wide range of businesses, including hospitals, dry cleaners, lawn care, clothing, and paints, as well as many types of consumer products. The author thought it quite possible that legislators would accept MCS (or “misperceive environmental illness as medically legitimate” as the paper states it). That could lead to “enormous cost,” the paper warned.

A particular threat was the expensive lawsuits from people made sick by toxic products.

The paper then provided an overview of the scientific controversy, which was substantial, as there was very little actual science available. Four medical societies had also issued statements critical of MCS.

A little ridicule was also used:

The basic fallacy in their reasoning is that the observed symptoms may be induced by many other causes. An equivalent example of such erroneous reasoning is that if a rooster crows every morning before sunrise, then the sun rises because roosters crow (pg 13).

What to do with the patients was very clear:

Emphasis should be placed on proper psychological diagnosis and treatment . . . (pg 14).

As for dealing with the press, the paper recommended:

Identify medical personnel familiar with environmental illness who can speak as experts . . . Informally offer guidance and background materials to reporters . . . (pg 15).

The paper then discussed the current thinking of the courts, which were almost universally dismissive of MCS claims of tort and disability at the time.

MCS activists had attempted to get help from the state legislatures in California, Connecticut, Maryland and Florida with modest success. Both chambers of the California legislature passed a 1984 bill to fund research into MCS, but governor Deukmajian was convinced to veto it (California Legislature 1984; Blonien 1984).

These attempts were a serious threat to the chemical industry and needed to be opposed (pg 20):

Legislators and respective staff should be wary of legislation attempting to review and redress the issue of environmental illness . . .

Environmental illness bills should be thoroughly critiqued . . .

When considering a bill, legislators should remember that environmental illness is a gray area, one which has not proven its existence in the medical area and one which has no precedence in state statutes.

The briefing paper concludes with the suggestion that the chemical industry forms a coalition with other industry groups that have “an interest in placing environmental illness in its proper perspective.” It suggests insurance companies, the pesticide/herbicide industry, food industry, auto industry, aerospace industry, cleaning agent industry, homebuilders and many more. It then states:

. . . a coalition with the state medical association is absolutely necessary (pg 22-23).

The briefing paper was intended for the CMA member firms and not for the public, but MCS activists quickly got hold of a copy. It was reprinted in the Fall 1990 issue of the MCS newsletter The New Reactor and is now also available on the web and in various archives.

This paper was a call for action to fight the acceptance of MCS, and the call was heeded.

The meeting

A meeting to discuss the MCS problem was organized by the industry lobby group the American Petroleum Institute (API 1990a, 1990b; Hileman 1991).

It was held on November 7 and 8, 1990 and was titled "Perspective on Environmental Illness: an industry forum."

There were six invited speakers: three industry lobbyists, a lawyer from the Mobil oil company, a director from the insurance company Aetna, and an allergist. The allergist had already publicly claimed that MCS "constitutes a belief and not a disease" (Terr 1987) and was regularly hired by various insurance companies to dispute MCS disability claims (Terr 1986, 1989).

Little about the discussions leaked out, but the talking points from two of the lobbyists have survived (Risotto 1990). They highlight that the Indoor Air Quality Act then under consideration by the House of Representatives would directly legitimize MCS. (The Act died in committee, perhaps due to lobbying efforts.)

A lobbyist gathered the names of three physicians willing to speak against MCS on scientific panels (Holm 1990).

The tobacco industry

The tobacco industry also became concerned about MCS. The deadly effects of smoking were clear with the Surgeon General’s report in 1964, but the industry fought a campaign of disinformation and obfuscation for decades afterwards. Every time they were taken to court, they simply argued that smoking was a personal choice, and if it actually harmed the smoker, it was their own responsibility. In case after case, judges and juries accepted this argument. Big Tobacco never lost (Brandt 2007).

In the 1980s a bigger threat emerged: second-hand smoking. Science started to show that innocent bystanders could be harmed by smokers. Nonsmokers demanded smoke-free spaces. The first successful lawsuit against Big Tobacco was on behalf of flight attendants forced to breathe smoke aboard airplanes. The lawsuit resulted in the first smoking ban on airplanes in 1988 (Brandt 2007).

MCS activists in Arizona were involved in the first smoke bans (Rivera 2020).

Such restrictions were a direct threat to tobacco sales and were taken very seriously. The industry fought back by saying the government had no business telling smokers not to smoke wherever they pleased, and they hired scientists to say second-hand smoking was harmless (Brandt 2007).

In 1991 a tobacco public relations firm wrote a report on the threat from MCS. It spent five pages listing recent MCS grassroots activities and said that MCS was a direct threat to the industry. It stated that MCS could become an “explosive issue” and “the stakes are very high” for industry interests (MBD 1991).

Another call to arms was issued, and the tobacco industry joined the fight against MCS.

Forbes magazine

The new anti-MCS tone in the media appeared to start with a front-page article in the July 8, 1991, issue of Forbes magazine (Huber 1991a).

It compares MCS with tabloid stories of Princess Diana having an affair with Elvis Presley, and similar questionable ideas. One graphic shows a man freaking out when seeing the smoke plume from a large factory chimney.

It uses strong language and the term "chemical AIDS" throughout the article, such as in:

... it's politically convenient for chemophobes to embrace the junk science of chemical AIDS.

This may be the first use of the term "junk science," which basically means any science that threatens corporate or political interests.

The article derides some other issues that have since become more accepted, such as the chemical PCB (polychlorinated biphenyl). It also stated that health effects from power lines were a new and pending issue.

The article ends comparing lawsuits with witch hunts and the Spanish Inquisition.

The Chemical & Engineering News article

Just two weeks after the Forbes article, the industry magazine Chemical & Engineering News had a seventeen-page article about MCS. Surprisingly, it was a balanced article with input from people both dismissive and supportive of MCS (Hileman 1991).

It is a landmark article that describes the situation in 1991, where the issue had become so emotionally charged in the medical community that constructive dialogue was very difficult.

The article lays out the financial risk (pg 31):

Clearly, the economic stakes in this issue are very high . . . the chemical industry and other industries whose products seem to cause the illness could be faced with many more thousands of very costly lawsuits.

And there would be many other costs — to the individual . . . to the employer . . . to manufacturers . . . to building owners and managers . . . to the government . . . to medical insurance companies.

A spokesperson for a national MCS support group is quoted saying that they are contacted by five hundred new people each month who inquire about how to deal with MCS. Ten years before, it was a hundred each month. The problems seemed to be rising.

Industry front groups join in

The American Council on Science and Health (ACSH) published two anti-MCS booklets, one was titled Unproven "Allergies": an Epidemic of Nonsense (Barrett 1993; Orne 1991, 1993). They also sent out a press release warning about "doctors cashing in on environmental illness" (ACSH 1993).

ACSH labeled itself as "nonprofit" and a "consumer education and public health institution directed and advised by over 200 prominent American physicians and scientists." However, Consumer Reports (1994) pointed out that ACSH had strong financial ties to the chemical industry and had argued in favor of many controversial products made by its funders, such as artificial sweeteners, growth hormones, urea formaldehyde foam insulation (UFFI), asbestos, and various pesticides, including DDT. Later, ACSH also defended formaldehyde, the phthalate DEHP, the Teflon precursor PFOA, and much more (McGarity 2008; Stauber 1995; Rampton 2002).

Another organization was The Advancement of Sound Science Coalition (TASSC), which was created in 1993. When the state of New Mexico wanted to study whether MCS should be considered a disability, representatives of TASSC opposed the study by claiming enough had been done already (Carruthers 1996a, 1996b).

TASSC was started by the tobacco company Philip Morris to oppose regulation of tobacco, which ACSH actually refused to do. In order to appear more respectable, TASSC solicited other corporations for donations and worked on opposing regulations of greenhouse gases, air pollution, food additives, and much else (Michaels 2008; Davis 2002: ch 7; TASSC 1998; Rampton 2002).

Another actor that showed up to oppose MCS was Responsible Industry for a Sound Environment (RISE), which was organized by the pesticide industry, including Monsanto, Sandoz Agro, DowElanco, Dupont Agricultural Products and others (McCampbell 1996, 2001; Rachel 1995).

There were also front groups more narrowly focused on opposing meaningful standards for indoor air quality and any form of “source control” (i.e. restrictions on tobacco, building materials, furniture, etc.). This included discrediting people who got sick from poor indoor air, especially people with MCS.

Total Indoor Air Quality

TIEQ was started in 1991 by the R.J. Reynolds tobacco company, which hired a public relations company to do the actual work and staffing (Harrison 1991, 1992).

By 1993 they had signed up 18 additional companies as members and had a six-month budget of $243,000 (Caldera 1993).

They spent about 80% of their time on “developing and maintaining good communications with … the press” (Caldera 1993).

They worked by casting doubt on the science and claiming that all health effects from poor indoor air quality “simply hasn’t been proven” (IAR 1992).

They also monitored Congress and governmental agencies to warn their members about laws and regulations in the works (“to head off misguided legislative and regulatory activity” as they called it) (Harrison 1994a, 1994b).

This included lobbying against the second attempt at creating a federal law on indoor air quality (Harrison 1994b).

They co-sponsored an anti-MCS symposium held in Washington, DC (see later) (Logue 1992; Harrison 1992) and funded the activities of MCS-opponent Dr. Ronald Gots (Harrison 1992, 1993).

Business Council on Indoor Air

BCIA was created in 1988 as a front group for the chemical industry. Their active members included Dow Chemical, Union Carbide, Amoco, Owens Corning Fiberglass and others (BCIA 1990, 1992; Hamilton 1991). The infamous Tobacco Institute was a member through a middleman (HBI 1993), and “briefed” them on tobacco issues (Packett 1993).

BCIA had six employees and produced a quarterly newsletter named Indoor Air Bulletin (SourceWatch).

Their purpose was to oppose any sort of legal standards for indoor air quality, and any restrictions on chemicals in building products. This meant they needed to discredit MCS and sick building syndrome.

BCIA fought against the acceptance of MCS behind the scenes, using lobbyists that worked to influence government officials (Risotto 1990; Holm 1990; BCIA 1991).

They produced an anti-MCS document “for use on the Hill,” i.e. U.S. Congress staffers (Hamilton 1991).

One ongoing argument for doing nothing to help the sick people was MCS needed to be “studied much, much more” (Hamilton 1991). Of course, money for such studies never became available. Always asking for more studies is standard fare from all sorts of industries trying to prevent any sort of regulation (Michaels 2008).

BCIA sent two lobbyists to a National Academy of Sciences meeting on MCS (Holm 1991).

When the federal agency Housing and Urban Development (HUD) officially accepted MCS, the BCIA worked to change the agency’s mind (BCIA 1992; Cammer 1992; Mansfield 1991).

In a letter to HUD, they included three anti-MCS papers, including one produced by BCIA itself. They also included the notorious Iowa study (see later).

The letter refers to a personal meeting between the BCIA president and a HUD representative on this matter the month before, and concludes with this statement (Cammer 1992):

We would greatly appreciate a correction of the guidance document sent previously to your district offices. I will call you in a week or so to discuss this request.

This refers to the internal HUD document that fully accepts MCS as a legitimate illness (Weidenfeller 1992).

The BCIA effort apparently worked, as HUD became much less friendly to people with MCS. This was important, as HUD support was crucial for the sick people to be accommodated in government-subsidized housing. Disabled by MCS, many could no longer afford regular housing.

Environmental Sensitivities Research Institute

The Environmental Sensitivities Research Institute (ESRI) was founded in 1995 by Dr. Ronald Gots. He was also president of National Medical Advisory Service which assisted companies who were sued by people with MCS. The two organizations had the same street address in a suburb of Washington, D.C. At the ESRI kick-off meeting Gots described MCS as "a peculiar manifestation of our technophobic and chemophobic society" (Risk Policy Report 1995a).

ESRI was clearly created specifically to fight acceptance of MCS. They did no research but focused on disseminating anti-MCS opinions in sponsored newspaper articles, court cases involving MCS and at various medical conferences. They also sent representatives to testify against MCS when legislatures debated funding research or accommodations for people with MCS (Donnay 1997; McCampbell 2001; Ashford 1998).

In a letter to a Governor’s Committee in New Mexico, a representative of ESRI announced that she would travel to Santa Fe to attend their Town Hall meeting on MCS. She included some of ESRI’s materials about MCS and stated, “our interest is to add some much needed scientific balance to what is often an emotional issue.” She also offered the help of what she referred to as “independent experts” (Richard 1996).

ESRI produced various small brochures. In one they stated that:

[MCS] is a symbol of societal unrest, distrust of technology, fear of chemicals, environmental worries and the pervasive sense of victimization (ESRI undated 1).

Another brochure is much more nefarious. Titled “The facts about multiple chemical sensitivity (MCS),” it states:

[T]hey are experiencing a psychological reaction to an odor they do not like or which holds unpleasant associations … MCS sufferers may be sensitive one day to one substance, and not sensitive to it the next day (ESRI undated 2).

The true origin of this brochure was not disclosed. Instead, it bears the stamp of the American Academy of Family Physicians Foundation and a statement that it was “reviewed favorably” by them. When the Foundation discovered ESRI was hiding themselves, they withdrew permission to use their name (McCampbell 2001).

ESRI placed an ad in newspapers across the country. It was made to look like a story from a news agency (Ashford 1998: ch 9; Donnay 1997). It stated:

Many established scientists and physicians doubt MCS actually exists; it exists only because a patient believes it does and because a doctor validates that belief.

ESRI also paid for a special supplement about MCS in the medical journal Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology (Ashford 1998: ch 9). It included an article about how NOT to accommodate people with MCS in the workplace (Dolin 1996), as well as two articles apparently produced by Dr. Gots (Anonymous 1996; Gots 1996).

Dr. Gots specialized in indoor air quality problems, including helping companies with sick buildings. He was involved with industry groups that resisted regulating indoor air quality, including TASSC (Catalyst 1995) and TIEQ (Logue 1992; Harrison 1991, 1992; IAR 1992).

Dr. Gots was a prolific writer of opinions on MCS in medical journals (Gots 1993a, 1993b, 1996, 1997) as well as at conferences (Gots 1992a, 1993c; Logue 1992; IE 1993; Wilson 1996; IPCS 1996).

He wrote the 1993 book Toxic Risks: Science, Regulation and Perception. It was reviewed by the Journal of Occupational Medicine, which was not known to be friendly towards people with MCS. The review was scathing, ending with these words:

Dr. Gots’s attempt to provide a broad perspective has failed. An objective, balanced, scientific, and detailed evaluation of the issues … was compromised by oversimplification and the interjection of Dr. Gots’s own strong personal opinions and perceptions (Teichman 1994).

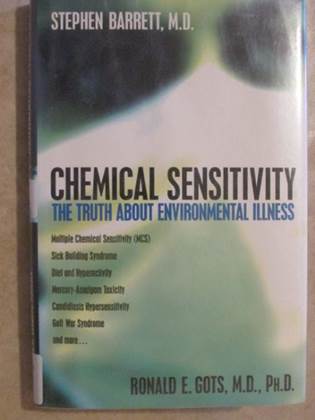

He also co-authored the book Chemical Sensitivity: The truth about environmental illness. The other co-author was Stephen Barrett, who also produced anti-MCS materials for ACSH (Barrett 1993; Orne 1993).

Gots and Barrett wrote:

“Multiple chemical sensitivity” is not a legitimate diagnosis and is not caused by environmental chemicals. It is a phenomenon in which people misinterpret irritant or stress responses as “allergies” or “toxicities” and alter behavior abnormally (Barrett 1998).

ESRI was secretive about its membership and sponsors, but it is known that its board of directors included several representatives from the chemical industry (Donnay 1997; Ashford 1998: ch 9; McCampbell 2001).

The tobacco company Philip Morris contributed $323,975, cumulatively (Huggins 2001a, 2001b).

Lobby Organizations

Besides the front groups that tried to disguise themselves as grassroots organizations, there were also the regular lobbying groups.

In 1990 the Chemical Manufacturer’s Association (later American Chemistry Council) employed twenty full-time lobbyists to work on behalf of their 175 member companies. They were also in the process of establishing a Political Action Committee to buy political candidates (Reactor 1990).

They spent $5 million on lobbying each of the years 1998 and 1999, the earliest years such data is available (Open Secrets).

Some of this political lobbying muscle was undoubtedly used against people with MCS, since this was the organization that raised the alarm within the chemical industry (Credon 1990).

Another apparent lobby heavyweight was the American Petroleum Institute, since they organized the 1990 MCS forum (API 1990a). They spent about $3 million dollars on lobbying in 1998 and 1999 (Open Secrets).

Then there were the individual firms. Dow Chemical, which was actively supporting the front group BCIA, spent more than two million dollars a year on lobbying in the late 1990s (Open Secrets).

Public relations firms

Public relations firms work to manipulate the public opinion on behalf of their clients, which can be large corporations, government agencies, interest groups, politicians, and even foreign countries (especially dictatorships). Some firms specialize in crisis management, such as when a corporation is targeted by a grassroots organization or some scientist publishes a study that can negatively impact sales. These firms were very active and effective around this time (Stauber 1995; Rampton 2002).

They work behind the scenes so the public is not really aware how much their perception of an issue is actually shaped by manipulation. They also help hide how much money and effort a corporation spends on this, as “public relations” is not “lobbying.”

For some campaigns they work with advertising companies. Many of them are actually owned by large advertising companies. Most of their work is manipulating the media. They contact journalists and offer them easy-to-use information and referrals to “independent experts.” Journalists are always pressed for time, so they like these flacks who can save them a lot of work building a story.

In 1994 the top fifteen public relations firms in the United States charged about a billion dollars in fees (Stauber 1995: appendix A).

One of these firms that was hired to change the image of people with MCS was E. Bruce Harrison. It specialized in opposing any kind of environmental issue. Previously it was hired to discredit Silent Spring author Rachel Carson, and organize front groups opposing the acceptance of climate change and emissions controls on vehicles (Stauber 1995).

Now it was hired by R. J. Reynolds to create and staff the front group TIEQ and funnel money to the outspoken MCS opponent Dr. Ronald Gots (Harrison 1991, 1992, 1993).

Mongoven, Biscoe and Duchin (MBD) specialized in “public policy intelligence.” The firm subscribed to as many grassroot activist newsletters as possible, to keep track of who the leaders were and what their policies were. The firm even employed people who posed as members to gather information (Stauber 1995).

MBD also reported on the activities of the MCS activists (MBD 1991).

The BCIA front group worked with at least three public relations firms: Sparber and Associates, The Meckler Group, and Paul, Hastings, Janofsky and Walker (Hamilton 1991).

Shell Organizations

There were apparently also some shell organizations that were just used to reroute money, so it was difficult to find out who actually funded all this manipulative work. One such was the Environmental Issues Group (Cammer 1993).

The tobacco industry’s own efforts

Besides creating the front groups TASSC and TIEQ, the tobacco industry made its own efforts to discredit MCS.

A professor at George Washington University claimed in a medical journal that when people with asthma or MCS were sickened by cigarette smoke, it was simply psychosomatic (Witorsch 1992a).

The article did not disclose the professor’s financial ties to the infamous Tobacco Institute (Witorsch 1992b; Packett 1993; Brandt 2007). That was first made public later when internal industry documents were handed over during lawsuits (see later)

A draft of the article was sent – before publication – to the tobacco company Philip Morris. The anti-MCS section was sent separately for input (Witorsch 1991).

The same professor also wrote a chapter in a book about lung disease. The chapter strongly suggested that MCS, sick building syndrome, and chronic fatigue syndrome were all psychosomatic (Witorsch 1994).

He also wrote at least two other articles with MCS in the title, though we have not been able to obtain copies. One of the titles is “MCS: a name in search of a disease.” This slogan was picked up by others (Bovard 1996; Epstein 1994).

Philip Morris also produced a “briefing book” about smoking restrictions. It was intended to provide cigarette-friendly talking points to politicians and other influencers. It complained about “discrimination against smokers” and claimed that the science documenting health effects was “inconsistent” and “unconvincing.” It also had two pages denigrating MCS, saying it is “a manifestation of one or more common mental disorders” and there is “no evidence” cigarette smoke can trigger MCS symptoms (Philip Morris 1997).

In the 1990s, the U.S. Congress and the Environmental Protection Agency attempted to improve the indoor air quality in workplaces. One proposal was a voluntary program called BAQA. Restricting tobacco use was a cornerstone in these programs. The tobacco industry was instrumental in blocking all these attempts (Brandt 2007; IAR 1992; PM associate 1996; MBS 1995; Merlo 1995).

The tobacco industry and its public relations outfits worked tirelessly to influence journalists and editors by meeting with them, and often taking them to lunch (BM 1990; Parrish 1993; Harrison 1992). They apparently sometimes offered money; we know this because of an internal note about a pundit who refused to be controlled by Big Tobacco (Donohue 1993). They were otherwise too smart to put such bribery on paper.

The New York Times was able to document how the tobacco industry had hired major Hollywood stars to smoke their cigarettes onscreen. The agreements were never on paper, the payments were “gifts” of expensive jewelry, cars, and horses (Hilts 1994).

We don’t have transcripts or recordings of these private meetings, but there is no doubt that denigrating people with MCS was a part of their spiel to convince the media and officials that there was no need to improve indoor air quality.

Galileo’s Revenge

The book Galileo’s Revenge was an influential attack on scientific findings that threatened corporate America, especially the tobacco and chemical industries. Such findings were referred to as “junk science.”

The book had an entire chapter attacking the credibility of MCS, using the language of outrage and ridicule (Huber 1991b).

The entire book used the same tools of half-truths and manipulation it accused others of using. The author was based at a Washington think tank, The Manhattan Institute, which was heavily funded by the tobacco industry (Rampton 2002). Thus it is not surprising that the book doesn’t mention the biggest producer of science-for-hire: the tobacco industry, or any other industry doing it.

The same author, Peter Huber, then co-edited the book Phantom Risk: Scientific Inference and the Law, which also had a chapter about MCS. Other chapters discussed asbestos, dioxin, pesticides, power line radiation, nuclear power, and other issues of public concern.

This book was apparently organized by the tobacco industry, as part of their overall campaign to discredit science. Three years before the book was published, an outline was faxed to the tobacco company Philip Morris from the tobacco public relations firm Burson-Marsteller (BM 1990). The working title was then “Science and the Law” before it got its more snarky title.

Paid for editorials?

At this time it was rather common for medical scientists to be paid large sums of money to promote the interests of corporations. This included editorials, opinion pieces, public speaking, research grants, and more (Angell 2000).

The tobacco industry paid at least nine scientists to write letters to journals and newspapers supporting tobacco. They were paid up to $10,000 for each letter, which were often reviewed by company attorneys (Kaiser 1998). There are many similar stories from the medical industry (Rampton 2002: ch 8).

One scientist was contacted by a public relations firm and offered $2500 for a letter he didn't have to write himself, but would be published in his name. He refused and instead published the story (Brennan 1994).

The high-profile British scientist Sir Richard Doll was secretly paid $1500 per day by a pesticide company. In return, he maintained there were no health effects from the company’s products (Boseley 2006; Greene 2017).

A study published in the prestigious medical journal JAMA, concluded (Bekelman 2003):

Strong and consistent evidence shows that industry-sponsored research tends to draw pro-industry conclusions. By combining data from 1140 studies, we found that industry-sponsored studies were significantly more likely to reach conclusions that were favorable to the sponsor than were nonindustry studies.

Richard Smith had been a medical journal editor for 25 years, including 13 at the prestigious BMJ (formerly named British Medical Journal) when he wrote about the corrosive influence money in various forms has on scientific results and how far those paying to get their materials published were willing to go (Smith 2006):

This is a disturbing finding. It suggests that, far from conflicts of interest being unimportant in the objective and pure world of science where method and the quality of the data is everything, it is the main factor determining the results of studies.

There have been many opinion pieces against MCS in medical journals and newspapers (Salvaggio 1994; Witorsch 1992b; Staudenmayer 1997; Sandler 1993; Rubin 1990; Kurt 1990). How many of them were hired guns is unknown. By nature such arrangements are kept secret. Only a few connections have been documented.

Medical journals have since cracked down on these things with stricter disclosure rules, but it is difficult since most experts have such conflicts these days (ICMJE 2019; Smith 2006). The popular media seem totally unconcerned about this problem.

Negative science

A handful of scientific reports were published in the early 1990s that suggested MCS was simply a psychological problem. They were frequently mentioned in newspaper articles about people with MCS, and sometimes the scientists were even interviewed. A handful of names kept showing up.

A review of these reports showed many errors in their methodology, and that they were jumping to conclusions, but that was ignored (Davidoff 1994).

It was usually not disclosed who paid for these studies. One does mention in the text that the airplane manufacturer Boeing paid for the study (Sparks 1990). At the same time, Boeing was fighting several lawsuits from employees who got sick with MCS (Nelson 1994).

Another was produced at the Monell Chemical Senses Center (Dalton 1999). This outfit claims to be “independent,” but their own website admits they are sponsored by about fifty large chemical corporations (Monell 2020). This report was clearly made to discredit people with MCS and neighbors who complained about fumes from chemical plants. It jumps to the conclusion that all such complaints are purely psychological, just because some people feel sick when told they are exposed to toxic chemicals.

Scientists are well aware that if their results are not pleasing to their corporate sponsors, their funding is likely to be cut, or at least not renewed (Michaels 2008).

The Iowa study

The most influential report came from the University of Iowa. It compared 26 people with MCS to a group of healthy people (controls). It found that 65% of the MCS group had a mental diagnosis now or in the past. In the healthy group only 28% had such a diagnosis (Black 1990).

This looks like a strong case for the “all in their head” camp, and it was presented as such. According to Google Scholar, this study is referenced by no less than 297 scientific papers.

In those days universities rarely sent out announcements to the press when new research was published. But in this case, someone got the New York Times to write about the study on the same day it was published. The journalist interviewed the lead author, who stated: “It’s my belief that people diagnosed as having environmental illness in most cases do have something wrong: a garden variety emotional disorder” (NYT 1990).

This was in the days when newspapers were sympathetic to people with MCS, so the journalist also interviewed two physicians who rebutted Dr. Black’s assertions (NYT 1990).

This study had a lot of flaws. First of all, it was a small number of people. And it was really only 23 people, not 26. And another three MCS patients came from a psychiatric clinic, obviously skewing the group towards more mental health issues.

Comparing the MCS patients to a group of healthy volunteers further skews the results. As a physician who actually treated people with MCS commented:

I don’t think there’s ever been a study done comparing healthy community members with a group who suffers from chronic illness that hasn’t found psychopathology among the patient group – being sick tend to make people depressed (NYT 1990).

Stated more graphically, this and the later studies like it, were like studying Jews in Nazi Germany, and comparing them to non-Jews. And then concluding that German Jews were prone to anxiety and imagined worries.

The Iowa folks should have compared the MCS patients with a group of people with other life-altering diseases, such as severe asthma, burn victims, or people disabled from auto accidents. Surprisingly, later studies repeated the same fundamental error. Or maybe that was by intent, to be sure to reach the same result each time.

The questionnaires they used label people as mentally sick, if they have the common MCS symptoms. This is even if the person is known to not have any mental illness (Davidoff 2000). The Iowa study, and all those like it, will therefore overstate how many people with MCS also have mental illnesses.

The article also used opinionated language rarely seen in medical journals, and never considered what if these patients were not lying! The scientist had clearly made up his mind beforehand; he even admitted it to a journalist (NYT 1990).

It is surprising this article made it past peer review and got into such a prestigious medical journal.

Also keep in mind that in the recent past physicians were also convinced that asthma, eczema, hives, stomach ulcers, migraines, and much else were also largely mental illnesses (Nieder 1986; Noonan 2015).

Dr. Black then promoted his opinions in newspapers and magazines (McIntyre 1992; Hall 1993), as well as at a notorious anti-MCS medical symposium (Gots 1993a; Logue 1992).

Thirty years later, Dr. Black admitted he had only seen a handful of MCS patients over his entire career – other than the 1990 study participants, which he later published two more articles about. Despite that, a journalist labeled him “the de facto leading professional on MCS” (Xi 2022).

It is notable how much influence this single study had. That can only be ascribed to its promotion in the right places, and a receptive audience who wanted to believe MCS was not real (Cammer 1992).

Meanwhile, studies that did not find these high levels of psychiatric problems in people with MCS were ignored by the media and elsewhere (Fiedler 1992, 1996; Davidoff 1996, 1998; Caress 2002).

The childhood trauma theory

Two outspoken MCS opponents, psychiatrist John Selner and psychologist Herman Staudenmayer, did a small study that showed women with MCS were more likely to have had childhood trauma (Staudenmayer 1993).

The participants were largely recruited through Selner and Staudenmayer’s psychiatric clinic, so it is doubtful this group was really representative of the MCS population.

Worse, half of the women who supposedly reported childhood abuse did that through “repressed memory therapy” (Staudenmayer 1993, fig 3). That method has been thoroughly discredited as producing false memories (Brody 2000; Ley 2019).

Nonetheless, the idea that MCS was simply unresolved childhood trauma was promoted in medical journals, conferences, and popular media (Staudenmayer 1997; Epstein 1994; IPCS 1996; PM associate 1995; O’Mahony 1995).

Fourteen years later, the theory was finally tested with a larger study that didn’t rely on “repressed” memories (Bailer 2007). The theory did not hold up at all, but that result received no publicity, so the myth still lives on. In 2020 it was mentioned three times in a journalist’s shallow book about MCS (Broudy).

Provocation studies

Several studies exposed MCS patients to chemical fumes or supposedly inert placebos. The results were all over the board, which was used as “proof” that MCS is psychosomatic (Das-Munshi 2006).

But most of the scientists who did these studies had little actual experience with MCS and conducted the studies so poorly they were like placing someone in a room with a cigar smoker, and then testing if they could notice whether there was also a cigarette smoker there or not.

These kinds of tests seem easy, but in reality they are very difficult to do correctly (Goudsmit 2008). One major problem is that all sorts of people tend to report symptoms when they expect to be sickened, even if they are given an inert placebo. In a large cancer study, lots of people given a placebo vomited and lost their hair because they saw that happen to other patients given chemo drugs (Fielding 1983). Nearly half of people giving a placebo in drug studies report symptoms they attribute to the inert pill (Howick 2018).

This is well known, but the people with MCS are expected not to do this. They are held to an impossibly high standard of perfection that nobody else are expected to meet.

Heavy-handed tactics

In 1992 the city of Oakland, California, wanted to make their public meetings accessible to people with MCS. They intended to include a brief statement on their meeting notices asking people to voluntarily refrain from wearing perfumes in the room. The city was "hammered" by industry lobbyists and gave up on the idea (Hamilton 1994; O’Mahoney 1995).

The American Chemistry Council (formerly CMA) intervened in an MCS disability case that went to the Massachusetts Supreme Court, to set a precedent that doctors testifying in support of MCS were practicing “junk science.” This also yanked the disability pension away from a nurse with MCS (Ranalli 2000).

The ESRI front group even tried to silence one of the MCS advocacy groups by having a law firm send them a letter threatening a defamation lawsuit (Ebner 1996). The group, MCS Referral & Resources, replied that they were only stating the documented truth, and truth is not libel. They refused to back down (Donnay 1996). Nothing further happened.

The New Mexico campaign

Several people with severe MCS had fled to the clean dry air of New Mexico. They asked the state government to accommodate their needs, which resulted in the Governor’s Committee on Concerns of the Handicapped taking up the issue and holding hearings in 1996.

The possibility of a state officially recognizing MCS and perhaps restricting the use of fragrances, tobacco, pesticides, and other products really got the attention of the chemical industry.

TASSC, ESRI, the Cosmetic Toiletry and Fragrance Association, the Chemical Specialties Manufacturers Association, and the chemical manufacturer Ciba-Geigy got involved. Several sent representatives to Santa Fe to lobby and testify against MCS (Carruthers 1996a, 1996b; McCampbell 2001; Petrina 1996; Ziman 1996; Rhodes 1996; Richard 1996).

The local Chamber of Commerce sent out a “Chamber Alert” flyer to its members. It warned that accommodating people with MCS “could cost the state’s businesses millions” and asked their members to call their state legislators (ABQCC 1996).

The Committee quickly bowed under the pressure. The MCS community gained nothing more than a basic prevalence study that showed about 16% of the people in New Mexico had MCS (Voorhees 1998). It wasn’t even published in a journal.

Television turns negative

The tone in some media turned very negative. The American Broadcasting Corporation created several television programs dismissive of chemical pollution concerns and MCS. These included the programs Allergic to living (1991) and Allergic to the world (1997).

In one program, the journalist asks, "How does it feel to be getting money [disability] for a nonexistent condition?" (Lipson 2004).

For one of these anti-MCS programs, they attempted to entrap the MCS specialist Dr. Grace Ziem by sending two healthy women to pose as MCS patients, while wearing hidden microphones, but it backfired (Spangler 1996; Carter 1996a, 1996b).

The executive producer of most of these programs was married to a chemical industry PR agent, according to the watchdog Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting (Grossman 1994). The same watchdog also pointed out that these programs used fabricated data when lambasting organic produce (FAIR 2000). The industry front group ACSH also participated in at least one of these programs (Stauber 1995).

When the federal government funded a special apartment building for people with MCS, it was mocked by ABCs "house doctor" on a news program, as well as by the Cleveland Plain Dealer (Reactor 1994; Epstein 1994).

Newspapers turn negative

After all the sympathetic newspaper coverage in 1990, there was an abrupt change. From 1992 onwards there were few stories about MCS, and they were rarely sympathetic towards the sick people.

The stories now usually included a statement from a physician that MCS was just a mental illness. The physician was often from the same small group of outspoken anti-MCS physicians. It was suddenly rare that there was any statement from a physician who accepted MCS as legitimate.

Some newspapers went further and published stronger-worded anti-MCS opinions. The syndicated columnist Walter Williams wrote in The Washington Times, and many other papers, that people with MCS are “wackos” and “crazies” (Williams 1996). He ended his tirade with these words:

I know what I’d do to one of these multiple chemical sensitivity wackos attempting to make me wash off my aftershave.

Williams also railed against tobacco restrictions, but to his credit he refused to be bought by the Tobacco Institute (Donohue 1993).

Three weeks earlier a similar diatribe appeared in the Wall Street Journal by someone at the conservative think tank Cato Institute (Bovard 1995b; Williams 1996). Unfortunately, the full text is not available.

A couple of weeks later, he wrote another broadside against MCS, where he stated:

Because someone wears a respirator to work and gets hysterical six times a day, that supposedly proves that the person qualifies for protection under the ADA (Bovard 1996).

And

[MCS] is an allergy to the idea of anyone being allowed to wear perfume that generates the angst.

A few months earlier, Bovard wrote in The American Spectator:

Just as bad as the elevation of social pathologies to civil rights is the proliferation of new “disabilities,” among which “multiple chemical sensitivity” – to perfumes, aftershaves, and the like – is becoming one of the most fashionable (Bovard 1995a).

Even a magazine for restaurant owners ranted against MCS and possible

restrictions on fragrances and tobacco smoke (Kadow 1998).

The Boston Globe called MCS a “fad illness” and “total bull” in an article titled “Disease du jour” (Foreman 1996).

The Cleveland Plain Dealer also had a mocking article (Epstein 1994).

When a new apartment building for people with MCS opened, there were problems with some of the materials that bothered the residents. The press was all over that story (Adams 1995). Even years later, it was claimed that “nothing is ever enough” for people with MCS (Bovard 1996; Bandler 1998).

The building eventually became a great success with a long waiting list, and later such projects also worked well, but none of that was reported in the press.

An exception to this trend was The Chicago Tribune, which continued to show sympathy towards people with MCS (Goering 1991; Grow 1994; Garloch 1998).

The Washington symposium

A two-day symposium about MCS was held in Washington, D.C., in November 1992. It was organized by Dr. Gots’s National Medical Advisory Services, which had numerous times helped corporations fight in court against people with MCS (Gots 1993a; MCSRR 1995a).

The other co-sponsor, the International Society of Regulatory Toxicology, also appeared to be biased. Professor David Michaels, who studies how corporations cover up inconvenient science about their products, characterizes this organization as:

…an association dominated by scientists who work for industry trade groups and consulting firms (Michaels 2008).

This organization sponsors a medical journal, which is accused of bias in support of industry interests (Ladou 2007; Michaels 2008, 2020). This journal published several anti-MCS articles (Anonymous 1996; Dolin 1996; Gots 1993a, 1993b, 1996; Terr 1993; more).

A major sponsor was the R.J. Reynolds tobacco company, which covered its tracks by using two layers of middlemen, including the front group TIEQ (Harrison 1992).

There were seven featured speakers. None of them were supportive of MCS as a “legitimate” illness (Gots 1993a). Four speakers were well-known for their strong anti-MCS stances. One of them stated he thought MCS patients had a

morbid absorption with bodily functions with the illness being the center of their life (Logue 1992).

The tobacco company Philip Morris sent a “senior regulatory analyst” to attend. She wrote a detailed report which concluded:

[T]his symposium did not represent a balanced perspective on this controversial issue (Logue 1992).

The Baltimore symposium

Another medical symposium was held over three days in the fall of 1995. It was co-sponsored by Johns Hopkins University/NIOSH, and again The International Society of Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology, and the National Medical Advisory Service.

The National Medical Advisory Service was the main organizer of an event similar to the 1992 symposium. It supplied the co-chair, symposium coordinator, and an additional moderator for the symposium (MCSRR 1995a).

The symposium was stacked with speakers who were biased against MCS. This included the usual physicians, as well as two lawyers who had assisted several corporations to fight MCS claims. There were also speakers from the Dow-Elanco chemical manufacturer and the Aetna insurance company (Symposium Agenda 1995; MCSRR 1995a, 1995b, 1995c; Risk Policy Report 1995b).

The pesticide industry sponsored the symposium through their front group RISE (Rachel 1995).

The Aspen symposia

Two other conferences were held in 1994 and 1995 in Aspen, Colorado. They were broader and included sick building syndrome, chronic fatigue syndrome, latex allergies, etc. Both conferences were organized by the mental health specialists John Selner and Herman Staudenmayer, who were vocal opponents of accepting MCS (Aspen program 1994, 1995; PM associate 1995).

Changing the name of MCS

Another stacked meeting was held in Berlin in 1996. Here a new name for MCS was promoted to distance it from the chemical causes and make the illness sound more psychological. The new name was: idiopathic environmental intolerance.

The coup-like meeting was protested by the scientific community, including the chairman of the meeting. As a result, the World Health Organization did not adopt the new name – to this day (2023) the name is not used anywhere on the WHO website. But the name became widely used by those opposing MCS (Abrams 1996; Ashford 1998: ch 9; Wilson 1996; EI Wellspring 2020).

The story about this event is available via a link at the end of this document.

International

The campaign against MCS occasionally reached beyond the U.S. borders, such as the Berlin symposium mentioned above.

When the Provincial government of Nova Scotia, Canada, evaluated their funding for the MCS clinic in Halifax, the three physicians who were most vocally opposed to MCS in the U.S. tried to intervene. Fortunately, their letters had very little effect on the positive report and the clinic continued to be funded (Broder 2000).

MCS is today more accepted in Canada, Japan, and Europe than in the United States, though it’s not great anywhere.

A high bar to pass

The medical system has a very high bar to pass for acceptance of an illness, especially if it threatens established dogma. It does not deal well with uncertainties and does not consider the human cost. There are no grey areas; either there is accept or there is not accept. There is no middle ground where the system essentially says: “we don’t understand but let us give these people some benefit of the doubt.”

Instead, any doubt is used against the sick people. Perversely, the psychiatrists do not have to meet such a standard for labeling people as mentally sick.

During the AIDS epidemic in the 1980s, the American medical community was also quite content with standing back while watching thousands of people die every year as talking about AIDS would mean accepting gay people existed, which was politically impossible. That included the National Institutes of Health (France 2016).

Heavily outgunned

The pro-MCS advocates were heavily outgunned. People were sick and either using all their energies towards holding on to their jobs, or so sick they had to go on disability. Most were focused on getting along with the toxic world as best they could.

There were several national and regional MCS organizations, but few tried to do real advocacy work. The number of people who were able to sustain advocacy work for years were very few. Of particular note are Susan Molloy, Ann McCampbell, Mary Lamielle, and Julia Kendall.

They were no match for the industry’s juggernaut.

The result of the campaign

Falsely painting people with MCS as crazy was a masterstroke. It gives politicians, doctors, journalists, and regular people license to ignore anything a person with the illness says. If an activist speaks up at a public hearing, the people sitting on the dais simply disregard what is said – after all it is just the ramblings of a crazy person there at the microphone, they think.

Potential allies, such as environmental organizations, disability rights groups, and civil rights advocates, shy away, afraid to be tainted by association.

By the middle 1990s, progress for MCS halted. Government agencies and others that had been in communication with the MCS activists stopped returning phone calls. The media stopped reporting on MCS with sympathy. The activists ran into solid walls everywhere and became demoralized. Their push for recognition and civil rights fizzled out (Molloy 2019).

Funding for medical research dried up. Scientists who wanted to study MCS were told that "everybody knows" MCS is all psychological, so it doesn't make sense to spend money on research (Meggs 2017).

Without research, it is impossible to find the real mechanism of MCS, thus it remains a mystery and by default that means it must be “all in their minds.”

The professors Nicholas Ashford and Claudia Miller wrote in 1998 that scientific studies of MCS are:

[S]tymied by scientists and physicians with financial conflicts of interest [which] generally remain undisclosed (Ashford 1998; ch 9).

The U.S. Congress and Department of Veterans Affairs allocated funding in 1994 to build and operate an environmental control unit at a university. This was a crucial facility needed to prove MCS was a "legitimate" illness. But the money

was simply never released, with no reason given (Twombly 1994; McFarling 1994; Ashford 1998: ch 8). An effective way to prevent unpleasant scientific results is to make sure there is no funding for it.

A 2018 study found only 320 MCS research articles published in medical journals, while there were 7453 articles about chronic fatigue syndrome and 9846 about fibromyalgia (Hu 2018). Those two diseases are also controversial, but not a threat to powerful special interests.

The last major medical conference about MCS was held in 2001. It had sixteen presentations, of which only four did not clearly advance some form of psychological explanation (Kipen 2002; Hu 2018).

Many other such campaigns

Discrediting those who got sick by falsely claiming they are mentally ill is not a new tactic. It was also done against people with ergonomic injuries (Scalia 2000), workers building nuclear weapons (Michaels 2008: ch 16), and people campaigning for their civil rights (van Voren 2009; Calhoun 2021; Metzl 2009). Women dying from radium poisoning were accused of having syphilis and anxiety (Moore 2017).

Other methods were used to ignore workers with silicosis (Rampton 2002).

There are many other well-documented stories about how special interests have fought inconvenient truths – and were often successful. These are stories about Orwellian-named front groups, media manipulation, science-for-hire, captured politicians and agencies. The well-known examples involved leaded gasoline, asbestos, cigarettes, ozone-destroying freon, and climate change, but many more stories are not commonly known (Bohme 2005; Ladou 2007; Ratliff 2018; Castleman 1996: ch 2,3; McGarity 2008; Michaels 2008, 2020; Oreskes 2010; Smith 2009; Davis 2002; Stauber 1995; Rampton 2002).

Of particular concern is the harassment of scientists who discover that industry products are health hazards. Their integrity is questioned, their funding is cut, their careers threatened, and all sorts of roadblocks suddenly appear. That has a chilling effect on independent research (Needleman 1992; Davis 2002; Rampton 2002: ch 7&8).

A few of these sordid stories have been made into Hollywood films, such as Erin Brockovich (2000) and Dark Waters (2019). These stories are small potatoes compared to the stakes on both sides of the MCS acceptance.

When software giant Microsoft was in danger of being broken up by an antitrust investigation, it fought back with an elaborate campaign that made it look like spontaneous and widespread opposition. A whistleblower leaked the ruse, but it worked anyway (Rampton 2002).

Industry flacks even work very hard to influence what is taught in schools, so it downplays climate change and promotes industry-friendly viewpoints (Worth 2022).

For an example of how public health information is manipulated, consider breast cancer. There are all sorts of campaigns to teach women to check themselves, to get mammograms, and to raise money for “the cure.” But virtually nothing about how to prevent breast cancer. Prevention doesn’t generate money for the medical industry and shines an unwelcome light on the chemical industry.

Another example is autism. It was virtually unknown in 1950, now it’s an epidemic. The only plausible explanation is that something changed in our environment or lifestyle, but there is little interest in finding out what it is.

The echo chamber

The type of research that receives funding is what looks at the mental health of people with MCS. Oddly enough, these studies don’t compare their MCS subjects to people with other life-altering illnesses. They are thereby guaranteed to find people with MCS are more stressed, depressed, etc. How convenient.

This has helped to create an echo chamber in the psychiatric profession. Just as in any other group, people who think differently from the herd find it best to keep quiet. The echo chamber has become so strong that anything that contradicts the current dogma is ignored.

When scientists at Johns Hopkins University made a clever study, it was ignored. It clearly demonstrated that common psychiatric diagnostic methods falsely label mentally healthy people as psychosomatic, if they have symptoms similar to MCS (Davidoff 2000).

When psychiatrists compared a group of people with MCS to a group of people with schizophrenia, they clearly expected a lot of similarities. When they found none, they explained it away by accusing the MCS people of lying (Weiss 2017).

As mentioned before, the mainstream psychiatric profession was in recent decades convinced that diseases such as migraines, asthma, sickle cell disease, stomach ulcers, and many others were psychiatric. They blamed the mothers for causing their child’s autism. See the link below for more on this.

Dangerous quack therapies, such as “conversion therapy” and “repressed memory therapy,” were considered mainstream and commonly used by psychiatrists in the 1990s. They are now discredited (Brody 2000).

The campaign today

The campaign was so successful that not much has happened in the past twenty years. The TASSC, BCIA, TIEQ, and ESRI organizations have disbanded. ACSH has since defended corporate interests on many other controversial issues, such as climate change, fracking, sugar, and the “forever chemicals” PFAS and PFOA (Michaels 2020; SourceWatch).

It is only occasionally they raise their voices against MCS, as when in 2011 the Monell Chemical Senses Center called fragrance sensitivities "anxieties" that are promoted by some doctors (CMAJ 2011).

When the day comes that MCS again starts to be taken seriously, there is no doubt the campaign will quickly resurface in some form. The methods will surely be somewhat different as they have new powerful tools available to manipulate public opinion, such as social media “influencers” and today’s polarizing television channels. Public relations firms now produce videos that are offered to television stations, and used without telling the viewers the origin (Rampton 2002). It will be done slyly again, hiding who is behind it. Now there are new tools to completely hide who pays for the disinformation, such as donor-directed philanthropic organizations. Billions of dollars are at stake, while the cost of fighting the truth is much much cheaper.

Meanwhile, the media occasionally perpetuates the established myth that people with MCS are simply mentally ill. One example was published by The Guardian, which created the myth that there are typically two suicides a year in the MCS community in Snowflake, Arizona (Hale 2016). The myth has since been repeated in other media. (There were two suicides the year before their visit, but that was a one-time event.)

When Time magazine wrote about mass psychogenic illness, they used MCS as an example (Szalavitz 2012). Never mind that mass psychogenic illness mostly happens to teenagers, while people rarely get MCS before the age of thirty.

Also notable is an article in the conservative tabloid New York Post, which featured a model photo of a fearful man wearing a mask and a tinfoil hat (Laneri 2020).

It looks like the media hostility is now self-perpetuating: a journalist looking into MCS reads what the colleagues have written and is influenced by it being virtually all negative. Thus the echo chamber continues.

A strange thing happened when a long-time sufferer of MCS bequeathed $5 million to Harvard University to do MCS research. The university did a few low-cost studies that were not about MCS, and the bulk of the money quietly disappeared (EI Wellspring 2023). Would they have dared if it hurt any other patient group?

Otherwise, MCS has been ignored so much it has become invisible to most people. When the American Academy for the Advancement of Science discussed brain fog in 2024, MCS wasn’t mentioned, despite the name came from there (Economist 2024). Even a 2022 book about chronic invisible illnesses fails to mention MCS, while lamenting how doctors ignore and psychologize patients with autoimmune disorders, fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, and other more “accepted” diseases (O’Rourke). Of course, those diseases never faced the organized opposition that MCS does.

The leader of the campaign for India to become an independent country, Mohandas Gandhi, famously said:

First they ignore you.

Then they ridicule you.

Then they fight you.

And then you win.

The campaign against MCS was able to turn the clock back to the “ridicule” state again – for now.

Internal industry documents made public

Whistle-blowers in the 1990s made secret documents public that showed the tobacco industry knew their products were addictive and deadly long before the health authorities did. This gave lawyers the idea to demand more internal documents and make them public through lawsuits (Brandt 2007).

The result is an unprecedented insight into the tobacco industry’s shenanigans.

These documents are publicly available through various depositories, such as the Legacy project at the University of California, San Francisco.

These depositories have provided many revealing documents cited in this article. And yet, several documents we see mentioned or otherwise ought to be there, are missing. Apparently, they were able to shred those before the court order took effect. We could only wish there was such a trove of documents from the chemical industry and its front groups and PR firms.

They document that two of the seemingly independent doctors who opposed the acceptance of MCS were really paid by the tobacco industry. How many more were there that we haven’t discovered? Given how common such secret arrangements were, there must have been several others.

References

The references are listed at: www.eiwellspring.org/hist/CMA1990reference.htm

We have gathered some of the referenced industry documents at:

www.eiwellspring.org/industrydoc1990.html

More information

The story about the efforts to call MCS idiopathic environmental intolerance is at:

www.eiwellspring.org/hist/IEIstory.htm

For information about two dozen other diseases that were falsely psychologized, see: www.eiwellspring.org/misc/EIcontroversy.htm

Other stories from the anti-MCS campaigns are at:

www.eiwellspring.org/mcshistory.html

2017 (updated 2024)