The 1990 fight to allow people with MCS aboard airliners

In 1990 two women with MCS were not allowed to board airliners because of their

disability. The following lawsuits may have helped future travelers with MCS.

Keywords: air travel, airline, chemical sensitivity, MCS, discrimination, access, lawsuit,

history, civil rights, Susan Molloy

Air travel difficult for people with MCS

An airplane packed with passengers can be a nightmare for someone with chemical sensitivities. People sit close together and if the plane is full it may not be possible to get another seat if a nearby person took a swim in a vat of fragrances that morning.

If the plane is rather new, there will be a toxic soup of chemicals offgassing from the plastic panels and the upholstered seats, including flame retardants.

The airlines encourage their flight attendants to be highly groomed, and their uniforms are treated with flame retardants.

While the plane is sitting on the ground, there can be jet exhaust coming in from the outside - especially at a major airport.

People with MCS have few options for coping. Most simply endure, or refrain from travelling by plane at all. Some bring some sort of mask or use bottled oxygen.

If you want to use oxygen or use a respirator, you should contact the airline well in advance. They may not allow you to board otherwise.

The situation in 1990

In 1988 smoking was banned on flights of less than two hours inside the United States, and later it was banned on all flights. This helped, but at the same time the airlines started saving money by recirculating the air coming out of the overhead nozzles. Soon passengers and flight crews complained about the fetid air (Tolchin, 1993; Portnoy, 1993; Flash, 1992).

The magazine Consumer Reports tested the air on 158 regular commercial flights and found it stale, dry and with air pressure as if on an 8000 ft (2500 meter) mountain. They noted that the cockpit had much better air quality than the rest of the plane, and some airplane types were better than others (Consumer Reports, 1994).

Unsurprisingly, the airline industry published their own report that contradicted Consumer Reports (Sharn, 1994).

The issue has not come up in the media in the following decades. This may mean the airlines quietly improved the air quality, but it could also simply be because the media lost interest.

The Americans with Disabilities Act passed Congress early in the year 1990. This landmark bill forbids discrimination against people with disabilities.

MCS had been reported in the media for several years, especially in California that was the center of a movement to get the illness accepted so people would be accommodated and funding made available for medical research. These efforts were met by fierce resistance by some parts of the California medical establishment. In 1981 the California Medical Association issued a statement dismissive of MCS.

This was the setting for the following story.

The flight of Susan Molloy

Susan Molloy lived in Marin County north of San Francisco and was an activist for the civil rights of people with environmental sensitivities. At the time she was the editor of the quarterly newsletter The New Reactor.

The medical society America Academy of Environmental Medicine held their annual conference in Coeur d'Alene, Idaho, on October 28 to 31, 1990. They invited Susan Molloy to make a presentation on civil rights and MCS.

When exposed to jet exhaust and other toxic fumes, it can affect Susan Molloy's central nervous system so she loses her ability to speak or walk. She may even have uncontrolled movements of her hands and arms (choreoathetoid movements). To lessen the impact she needed oxygen onboard the aircraft and to be transported in a wheelchair. The oxygen would provide her with a source of unpolluted air and make her more resilient against the toxic air inside the airplane.

It was not legal to bring one's own oxygen on board, since the canister could hide a bomb. The rule was that the airline had to provide it.

A group of physicians from San Francisco were attending the same conference, including Susan Molloy's physician. They travelled together on the same flight, which was with United Airlines.

Sixteen days before departure she bought her ticket. She informed the ticket clerk about her need for oxygen and that she would be using a wheelchair.

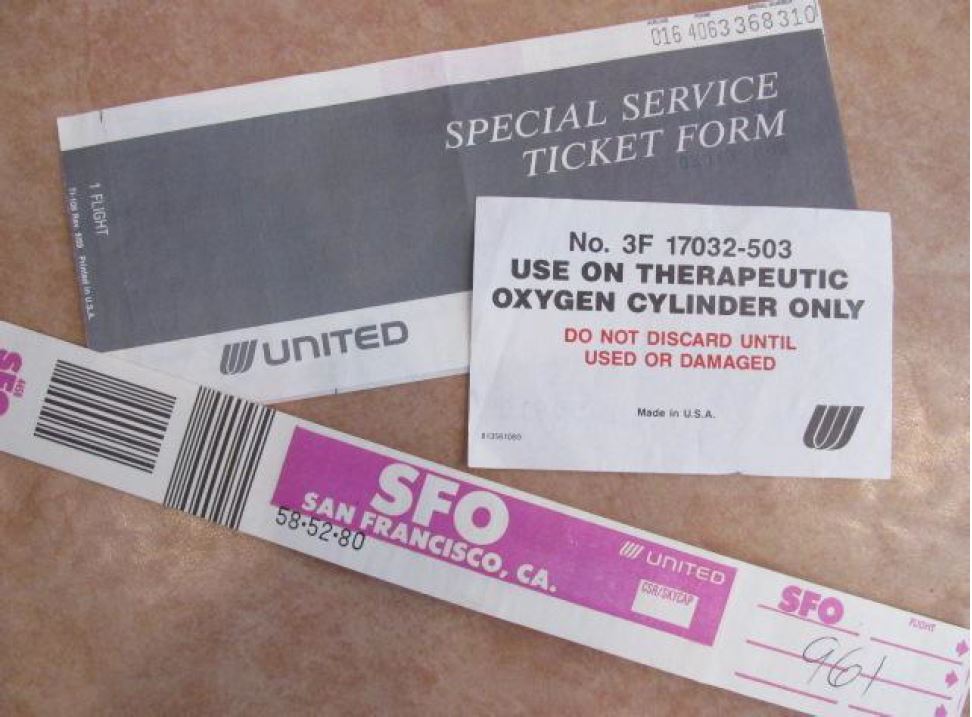

Various airline tags used by Susan Molloy on her trip to Coeur d'Alene.

Eight days before departure she called the airline's medical office to confirm she was a wheelchair user and needed the oxygen. She was told to bring a prescription from her physician when she checked in at the airport. Some days later the airline called to confirm the arrangements. Everything was in order.

About three days before departure, Susan received a message on her answering machine. Someone from the airline’s medical office informed her that their flight surgeon had declared her medically unfit to fly. They would not allow her to board the plane.

She spent the following days calling various parts of the airline to get this travel ban reversed. She told them her own physician would travel with her on the plane. She spoke directly to the flight surgeon who made the decision, but the ban was still in place.

Determined to go, she refused to let this stop her. She showed up in the airport anyway, bringing as much support as she could muster. This included her physician, two lawyers, her minister, a journalist and people from the Bay Area disability community. Given all this pressure the personnel at the check-in allowed her to board the plane and also provided the oxygen bottle (which she paid $50 for).

The plane landed in Spokane airport, where the group then continued on to Coeur d'Alene by ground transport. Susan Molloy was able to present her paper at the conference, as planned.

The return trip did not go so well. The group checked in at Spokane airport, Susan paid for her oxygen bottle and they moved on to the departure area. Then two security guards showed up, wearing the airline’s uniform. They informed Susan that their computer had ordered them to prevent her from boarding the plane, as she was on their "do not fly" list.

She was now faced with being stranded 700 miles (1000 km) from home, in a wheelchair, with no alternative means of transportation, and possibly with no support if the other people in the group flew back without her. Renting a car would be difficult, as that would mean many hours of toxic exposure and probably an overnight stay in a motel that likely would be toxic.

Wheelchair tags used by Susan Molloy on her flights to and from Spokane

Her physician, an attorney and other people travelling from the conference were able to convince the guards to back off and let her board the plane, but it was not easy. Had she not had all this horsepower to apply pressure, she would have been stranded.

The flight surgeon

The airline had several flight surgeons covering various areas of their worldwide operations. Apparently the flight surgeon stationed in San Francisco decided in early 1990 to oppose people with MCS.

On May 16, 1990, he sent out a brief internal memo to "all examiners" at the airline (RFS, 1990a):

Passenger oxygen is not an effective or appropriate treatment for "allergies" to the contents of cabin air. Do not approve oxygen for this purpose. Discuss these cases with me.

This document was discovered during the later lawsuit. What prompted him to issue this memo is unknown, though it could be because Susan Molloy flew to Washington, DC, that month and used oxygen on the flight (that flight was uneventful).

On October 23, just four days before Susan Molloy's flight to Spokane, he sent out a similar brief internal memo (RFS, 1990c).

In the interim he sent out a two-page memo where he discussed the use of oxygen for people with environmental illness, and that he considered it a placebo. Since he didn't think it was an effective treatment, he speculated that people with environmental illness might get so sick onboard the plane the crew would decide to make an emergency landing (RFS, 1990b).

The local PBS television station KQED aired a program about MCS in December 1990. It was titled "Bad Chemistry" and is one of the best documentaries ever made about MCS. It features several people with MCS. This includes Susan Molloy, who is shown having reactions to cigarette smoke and participating in a demonstration against biased physicians who were meeting at the San Francisco Hilton.

In his deposition, the flight surgeon admitted that he saw the program.

Filing complaints

Susan Molloy filed a complaint with the Access Board, a federal agency tasked with securing access for disabled people to public buildings and public transportation. They stated the complaint did not fall under their jurisdiction, and that they forwarded the letter to the U.S. Department of Transportation (Newton, 1990).

The Department of Transportation apparently never responded.

Susan Molloy then sent a complaint directly to the airline. The airline did look into the complaint.

The flight surgeon wrote a two-page internal memo in response to the complaint, it stated in part:

Basically, Ms. Molloy is the patient of a physician who holds an extreme, unorthodox and controversial theory of medicine which has been repudiated by the associations of the various legitimate medical specialties.

Most physicians believe that most of the people who feel themselves victims of these sorts of diseases are actually suffering from one or more mental disorders.

and near the end:

I have absolutely no apology to make to Ms. Molloy or to Dr. Anderson whom I believe to be at best deluded. (RFS, 1990d).

This memo was not forwarded to Susan Molloy. Instead, she received a vanilla apology.

Lawsuit

Susan Molloy contacted a lawyer who was friendly to the MCS community in the San Francisco area. It turned out that he was already working on a very similar case. Three months before Susan's flight to Spokane, another woman was prevented from boarding her plane solely because she had requested oxygen for her MCS. It was the same starting airport, same airline and same flight surgeon.

We contacted her for this article, but she asked use not to reveal her name or details of her story. (We have read the court documents, which are public records.)

Susan's lawsuit was filed in October 1991 in the Superior Court for the State of California in Alameda County. The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) first took effect in 1992, so they had to use older laws. They filed a civil rights case for discrimination against a physically disabled person by the airline, its flight surgeon and other employees It asked for injunctive relief, requesting that the airline ceases their discrimination against people with disabilities.

The airline hired the biggest law firm in California to defend itself. This was against a tiny law firm, with just one attorney who took the case on contingency, i.e. he would only be paid if he won. As the case dragged out he later had to bring in another law firm to share the case.

The airline’s attorneys asked the court to dismiss the case. Then they got it moved to federal court for the Northern District of California.

There was direct communication between the two law firms and informally the airline’s lawyers expressed sympathy for the women with MCS. It looked like it would all be settled quickly and amicably.

But someone higher up apparently nixed that. Abruptly, the friendly lawyers were replaced and the tone became much less cordial.

Not much happened for quite a while and it looked like the cases would go to trial with juries. The cases went into discovery in April 1992, where the airline provided some internal documents, such as the memos from the flight surgeon. The flight surgeon was also interviewed by the lawyer (deposition). It was here clear that even two years later, the airline and its flight surgeon had not changed any of their stances against people with MCS.

In May of 1992, the airline's lawyers offered to settle out of court, as it started to look like they could lose the jury case. But they offered a symbolic sum of money that did not even cover the legal costs. It was immediately rejected.

Then they tried intimidation by requesting that the plaintiffs "undergo physical and psychiatric examinations." This was an insult, and could result in dueling expert witnesses, as the airline would have no trouble finding a physician willing to state MCS was all in their minds. There was one in the area who had already done so several times. The request was refused.

The defense suddenly changed direction on June 22, 1992. They announced that the airline had changed its policy and would no longer override the traveler’s own physician. If the physician certified someone was fit to travel it would now be accepted. The airline would also no longer contest an oxygen prescription.

This satisfied most of the lawsuit, as it made it much more difficult to discriminate against people with MCS.

From there it took just two weeks before the parties met for a settlement conference where a deal was struck. The details of the settlement were sealed by the court and not available to the public (including this writer). It does not appear that anyone struck gold with this settlement, but expenses were covered. The important thing was to end the blatant discrimination.

Commentary

The conduct of the airline was clearly unreasonable, with blatant discrimination against two disabled people.

The outcome of this lawsuit may have circulated among the other airlines somehow, such as through their trade organization, trade newsletters, etc. It is likely the other airlines became aware of it, though we don’t know for certain.

We also don't know whether other airlines modified their own policies as a result.

Susan Molloy was never harassed again by any airline. In the following decade she made six or eight trips with oxygen and had no difficulty. She then became able to travel without oxygen. We know other people with severe MCS who since then have requested oxygen on their flight and had no trouble.

We also know people who simply advised the airline that they had MCS before they flew, and had no trouble getting another seat onboard to move away from overly fragrant people.

As for airlines harassing someone with MCS wearing a mask, we know of one case, which happened in 1993. It was a woman travelling on Swissair from Israel to the United States, with a layover in Zurich. She was forbidden to wear her mask on both flights. The airline apologized and suggested it would not have happened if she had let the airline know ahead of time she needed to wear a mask, so the crew could seek proper guidance before the flight.

There could easily have been other cases we don't know about. We suspect most people with MCS would simply chalk it up to just one more indignity bestowed upon them by a society that is often hostile towards people with this illness.

Our search of English-language newspaper websites in Europe and America found no stories about airlines harassing people with MCS. We did find several stories about people with other disabilities who had problems getting their oxygen onboard. They were stories of airline incompetence, inconsistent policies and predatory pricing. And there were stories about passengers who didn't do their part, such as bringing a doctor’s note and notifying the airline in advance that they intended to bring medical equipment onboard.

United Airlines changed their policy "voluntarily," they were not ordered to do it by a court. That means they were free to change it again as they wished. If they did, it hasn’t seem to be directed against people with MCS.

Sources and references

This story is almost fully based on the court documents, documents released through the discovery process and letters between Susan Molloy and her attorney. Some of these are listed below.

Susan Molloy provided some minor details verbally and she commented on a draft of this document.

Consumer Reports. Breathing on a jet plane, August 1994.

Flash, Cynthia. Strange in-flight illness hits some airline crews, Marin Independent Journal/McClatchy News Service, January 2, 1992.

RFS (1990a), Regional Flight Surgeon. Memo to: ALL EXAMINERS, May 16, 1990.

RFS (1990b), Regional Flight Surgeon. Consult: RE: USE OF O2 IN PASSENGERS REPUTED TO HAVE "ENVIRONMENTAL ALLERGIES," August 6, 1990.

RFS (1990c), Regional Flight Surgeon. Memo to: ALL EXAMINING STAFF, October 23, 1990.

RFS (1990d), Regional Flight Surgeon. Memo to: EXOPW – JAMES R. PALMER, RE: Ms. Susan Molloy Complaint of 12/7/90 (0433032A), December 17, 1990.

Molloy, Susan. Letter to Paul Rein, esq., describing her trip to Coeur d'Alene, June 7, 1991.

Molloy v. United Airlines, US DC case CV 92-0125 FMS.

Newton, Judith H. Letter to Susan Molloy from U.S. Architectural and Transportation Barriers Compliance Board, December 3, 1990.

Portnoy, June. Don't treat air quality in planes as a luxury, New York Times, (letters), June 17, 1993.

Tolchin, Martin. Frequent fliers saying fresh air is awfully thin at 30,000 feet, New York Times, June 6, 1993.

Sharn, Lori. Air on aircraft called safe, USA TODAY, April 29, 1994.

More MCS history

More MCS history articles on www.eiwellspring.org/history.html.

2021